EXCLUSIVE: A preview of Paul Preston‘s new book, ‘A People Betrayed. Corruption; Political Incompetence and the Breakdown of Social Cohesion. Spain 1874 to the Present Day.’

Behind the regime’s anti-corruption rhetoric, there was considerable profit to be made and not just at a local level. In 1924, Primo created the Consejo de Economía Nacional, an organism that did more to protect the existing interests of both industry and the big landowners than to promote development. Its ruling council consisted of a series of pressure groups representing staunchly protectionist Catalan and Basque industrialists and the agrarian elite. Similarly, the Consejo Regulador de Producción Industrial created in 1926 imposed state control over any new industrial enterprise effectively protecting existing corporations against new competition. Both tended to the creation of monopolies and with them, corruption. The easy-handed concession of monopolies saw fortunes made by Primo’s allies. José Juan Dómine, Juan March’s partner in the Compañía Trasmediterránea shipping company, paid for special trains to bring crowds to Madrid to take part in pro-regime demonstrations. Unsurprisingly, the Trasmediterránea received substantial government subsidies. Companies involved in the Dictatorship’s ambitious railway building programme were also the recipients of excessive subsidies.[1]

Ministers, senior military figures and elements of the Dictator’s single party, the Unión Patriótica did not hesitate to use their position, and the lack of a vocal opposition, to get sinecures or win lucrative government contracts.[2] According to Calvo Sotelo, in the Unión Patriótica, ‘there were crafty, hypocritical, professional frauds who had taken part for their personal benefit, despite their mental reservations’ (Había profesionales del dolo o de la cuquería que, llenos de reservas mentales, solo habían rendido su cerviz en sumisión hipócrita e interesada).[3]

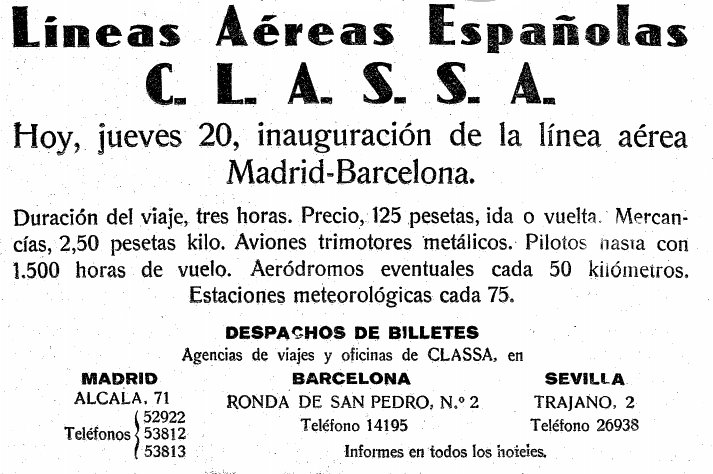

Needless to say, the corruption facilitated by the Unión Patriótica was small beer by comparison with that made possible by the links between big business and the government. Rafael Benjumea y Burín, the Conde de Guadalhorce, for instance, combined being Minister of Development (Fomento) with his position on the board of directors of the hydro-electric company Canalización y Fuerzas del Guadalquivir which, in 1925, received government funds to pay for half of its expenses. Guadalhorce’s brother Carlos profited from his investment in the company that built the highways from Oviedo to Gijón, from Madrid to Valencia and from Madrid to Irún.[4] A similarly favourable tax regime was accorded to another hydro-electric company, the Sociedad Saltos del Alberche, which Guadalhorce set up to build a dam on the Río Alberche west of Madrid. On its board of directors was to be found the Minister of War, Juan O’Donnell, Duque de Tetuán, who entered government debt-ridden and died a rich man in 1928.[5] Three other civilian ministers had profitable links with Banks, industrialists and landowners: José Calvo Sotelo (Finance – Hacienda) with the Banco de Cataluña and the Banco Central of whose board of directors he became president as soon as he left the government; José Yanguas Messia (Foreign Affairs – Estado) with the mine-owners and the Conde de los Andes (Economía) with landowners. The Dictator’s close friend, José Sanjurjo, was president of the company given the monopoly of civilian air transport in Spain, Concesionaria de Líneas Aéreas Subvencionadas, S.A. (CLASSA), whose profits benefited from government subsidies. It was alleged that Roberto Martínez Baldrich, the son of Martínez Anido, was given the monopoly of rat extermination and works of disinfection for the entire country, an inadvertently ironic commentary on Martínez Anido’s commitment to the extermination of reds.[6]

Martínez Anido was alleged to have accumulated a fortune during his time as civil governor of Barcelona. Someone who had incriminating information about him, Pedro Martir Homs, one of his henchmen in the organisation of assassinations during that time, was established in a flat in the Ministerio de Gobernación and paid a fat salary for a sinecure in the Telefónica.[7] Damning accusations were made in 1928 that huge amounts were made by friends of the King and of Primo in deals relating to major irrigation projects. It was alleged that the published price paid by the state for the Canal de Henares in Guadalajara and the Canal del Esla in León was wildly inflated relative to the real price, with the difference going into their pockets.[8]

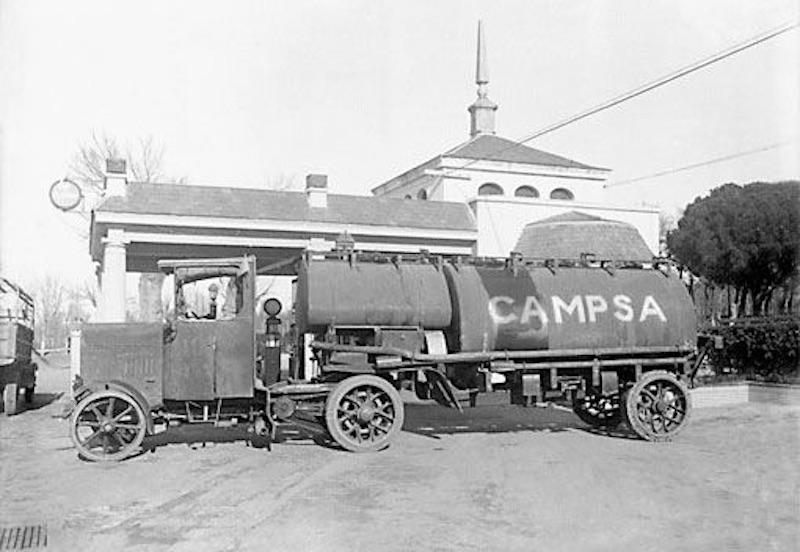

Some of the most curious ramifications of the Dictator’s obsession with creating monopolies were to be found in the creation of the state telephone and petroleum monopolies. The American Telephone and Telegraph Corporation was given the monopoly of Spain’s telephone services in August 1924. Granted generous subsidies and freedom from paying tax, ITT and its Spanish partners, all of whom had links to Primo, the Banco Urquijo, the Banco Hispano-American and the Catalan financiers the Marqués de Comillas and the Conde de Guell made huge profits out of the arrangement.[9] Once Calvo Sotelo was convinced by the idea for a petroleum monopoly, he put its implementation into the hands of his faithful collaborator, the lawyer Andrés Amado who worked with José Juan Dómine and Primo’s private secretary, Lieutenant Colonel José Ibáñez García. It meant going into battle with Royal Dutch Shell and Standard Oil. Needless to say, his initiative enjoyed the enthusiastic support of Juan March’s Porto Pi. Despite threats from the chairman of Shell, the Dutch-born Sir Henri Deterding, the assets and installations of the foreign giants were nationalised to create the Compañía Arrendataria del Monopolio del Petróleo, S.A. There was generous compensation for the commercial entities that it replaced, some of which, it was alleged, went into the pockets of Primo’s principal collaborators. Accordingly, CAMPSA was known popularly as the Consorcio de Amigos de Martínez-Anido y Primo, S.A. Even so, the operation was a success with the subsequent state revenue of CAMPSA more than doubling of that previously raised by customs duties.[10]

The father-in-law of Martínez Anido’s son was made an inspector of the monopoly in one province and one of his friends in another. Sanjurjo’s son was made inspector for Zaragoza. Primo secured León for himself. Lieutenant Colonel Ibáñez and another of his adjutants, Lieutenant Colonel Alfonso Elola Espín, were made national inspectors with fat salaries in addition to their military pay.[11] Martínez Anido’s adjutant, Roberto Bahamonde, was given the newly created post of Director General de Abastos (Supply) which allegedly opened up massive possibilities of corruption with Government suppliers having to pay a bribe to ensure contracts. Many similar profitable posts were invented for military comrades of the Dictator. Significantly, none went to artillery officers. When civilian courts looked into some cases of corruption, efforts were made to transfer them to military tribunals.[12]

In one of the most ill-advised, not to say comical, of his notas oficiosas, on 5 July 1929, the Dictator praised March’s patriotism for putting his fortune at the service of the regime. Hojas Libres was carrying out a campaign against March’s various dealings. A furious March complained to the Dictator and asked him issue orders to the frontier police to stop copies getting into Spain. To his dismay, Primo replied: ‘Don’t worry! I’ll sort this out with a nota oficiosa’ (¡Nada, hombre! Eso lo arreglo yo con una nota oficiosa.) To March’s horror, the next day there appeared a note saying ‘whatever the origins of this gentleman’s enormous fortune, the fact is that he has put it at the disposal of the Directory for any and all of its patriotic objectives’ (Podrá ser cualquiera el origen inicial de la cuantiosa fortuna de este señor; pero lo cierto es que desde que advino el Directorio la puso a su disposición para cuantos fines patrióticos o benéficos se le solicitara). The consequence was that massive publicity was given to both Hojas Libres and Primo’s flexible financial morality.[13]

There were also cases of fraud going unpunished thanks to the intervention of the government. One of several notorious examples was that of the Bilbao bank, the Crédito de la Unión Minera. As a result of administrative incompetence, irresponsible speculation, risky investments, the bank collapsed in 1925 with a debt of 92 million pesetas. Several senior bank officials had used deposits for their own ends. As a result large numbers of people were ruined. A judge, Pedro Navarro, was named to examine the role of the bank’s director, Juan Núñez and several directors who had made fortunes out of the affair. Among those arrested were the Conde de Abásolo, the Marqués de Aldama and the Conde de los Gaitanes, all friends of Alfonso XIII. The Conde de Floridablanca, the son-in-law of Aldama appealed to the King who immediately summoned the prosecutor of the Tribunal Supremo, the endlessly obsequious Galo Ponte y Escartín, and ordered him to arrange the release of Abásolo, Aldama and Gaitanes. Ponte went to Bilbao, ordered Navarro to free them, destroyed the dossiers of evidence against them and punished Navarro by having him transferred. Huge fines that had been levied on the accused were annulled by the Tribunal Supremo. It was alleged that the King received 1,500,000 pesetas for his part in the affair.[14]

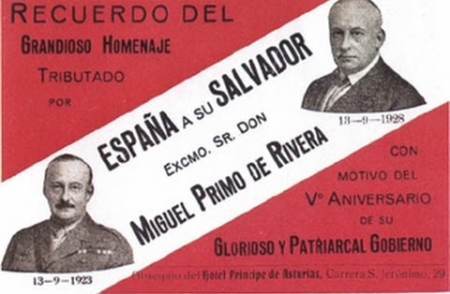

As time went by, corrupt abuse of government positions became more commonplace not to say more frenzied as it became clear that the regime’s days were numbered. Notorious examples ranged from the fortune spent on living arrangements for the Ministro de Marina to a national subscription organised by the regime to reward the dictator for his ‘sacrifices’ for Spain. Companies and banks were informed officially that their, ostensibly voluntary, contribution would be fixed according to their turn-over (volume de negocios).[15] On 9 March 1929, Primo issued one of his most naive and hypocritical notas oficiosas explaining that the purpose of the national subscription was to present him with ‘a house that would be a decorous location for my necessary repose after the hard struggle of recent years and also a solution to the needs of my family’ (una casa que fuera albuergue decoroso de mi obligado descanso tras la ruda lucha de estos años y solución adecuada del vivir de mi familia). Over four million pesetas had been ‘donated’.

His declared reason for drawing attention to this now was his proclaimed embarrassment that the enthusiasm of some of those behind the scheme had led to accusations that contributions were obligatory. Accordingly, he invited anyone who felt that they had been pressured into contributing to reclaim their money. Lest they be afraid to do so, he assured them that part of the money would go towards providing offices for the Unión Patriótica and the regional Somatén near his new house and also to the poor. Nevertheless, in justification of his acceptance of the gift, he declared that he had reluctantly allowed the subscription to go ahead because ‘more than anything else, although I was gratified by the idea of dying as poorly off as I have lived and live to this day, I went ahead with the scheme because, firstly, I believe in all conscience that my services to the country more than justify this beautiful homage; secondly, because I believe that it will be an example and a stimulus to those who come after me; thirdly, because I think that it is legitimate to ensure that my children do not have to move from apartment to apartment laden down with family heirlooms, as I have had to do, moving home in Madrid a dozen times; and fourthly, because I don’t want the Unión Patriótica and the Somatén to have to make do with rented premises.’ (más que nada, me halagaba la idea de morir tan modesto de fortuna como he vivido y vivo hasta el día, pero procedo así, en primer término, porque creo en conciencia haber prestado al país servicios que justifican este hermoso homenaje; en segundo, porque ello entiendo servirá de ejemplaridad y estimulo en el porvenir; en tercero, porque creo legítimo evitar a mis hijos que anden con la carga de gloriosas preseas y pergaminos, propios y familiares, de piso en piso, como he andado yo cambiando en Madrid una docena de veces de domicilio, y en cuarto, porque tampoco quiero que vivan de precario y alquiladas las oficinas contra los de la Unión Patriótica y el Somatén.) The idea that the Marqués de Estela, Andalusian landowner, had to permit this subscription lest he and his family be left in penury provoked not inconsiderable amusement.[16] At the end of September, it was announced that some of the money raised by the popular subscription had led to his being given a house in Jérez.[17] Four months later, he again exposed his naivety regarding the benefits of his position. He responded to criticism in Hojas Libres of the fact that his and Martínez Anido’s sons had enjoyed a junket to the United States as ‘representatives’ of the recently created Patronato de Turismo. He praised these young men for their sacrifice in making the trip.[18]

[1] España con Honra,No. 9, 14 February 1925, ‘Van saliendo los chanchullos’, Hojas Libres, No.6, 1 September 1927, pp. 84-7; Maura, Bosquejo, I, pp. 340-6; Calvo Sotelo, Mis servicios, pp. 256-60; José Luis Garcíá Delgado & Juan Carlos Jiménez, Un siglo de España: La Economía(Madrid: Marcial Pons, 1999) pp. 62-72; Ben-Ami, Fascism from Above, pp. 243-5.

[2]‘Algunas sinecuras de los renovadores’, Hojas Libres, No.7, 1 October 1927, pp. 75-8.

[3] Calvo Sotelo, Mis servicios, p. 332.

[4]‘Relación de chanchullos de la Dictadura (continuación)’,Hojas Libres, No.8, 1 November 1927, pp. 7-10.

[5]‘La Inmoralidad de la Dictadura’, Hojas Libres, No.15, June 1927, pp. 65-70; Maura, Bosquejo, I, p. 345; López Ochoa, De la Dictadura a la República, p. 161; Ben-Ami, Fascism from Above, pp. 245-6.

[6] José Luis Gómez Navarro, El régimen de Primo de Rivera (Madrid: Ediciones Cátedra, 1991) p. 170; Jaume Muñoz Jofre, La España corrupta. Breve historia de la corrupción (de la Restauración a nuestros días, 1976-2016) (Granada: Comares, 2016) p. 47.

[7]‘La torva historia de Anido’, Hojas Libres, No.2, 1 May 1927, pp. 81-6.

[8]‘Los últimos chanchullos’, Hojas Libres, No.12, March 1928, pp. 59-61.

[9] Saldaña, Al servicio de la justicia, pp. 169-76;

[10] Calvo Sotelo, Mis servicios, pp. 194-203; ‘Grandes negocios. El monopolio petrolífero’, Hojas Libres, No.4, 1 July 1927, pp. 74-6; ‘Primo y sus amigos. Estafa de más de dos millones de pesetas’, Hojas Libres, No.9, December 1927, pp. 24-5; Ben-Ami, Fascism from Above, pp. 248-50; Ramón Tamames, Ni Mussolini ni Franco: la dictadura de Primo de Rivera y su tiempo (Barcelona: Planeta, 2008) pp. 329-331.

[11]‘La Dictadura de Monipodio’, Hojas Libres, No.9, December 1927, pp. 45-8; Artur Perucho i Badia, Catalunya sota la dictadura (Barcelona: Publicacions de l’Abadia de Montserrat, 2018) pp. 308-10.

[12]‘Primo y sus amigos’, Hojas Libres, No.9, December 1927, pp. 24-9.

[13] Miguel de Unamuno, ‘Democracia y cleptocracia’, Hojas Libres, No.19, 1 January 1929;Gabriel Maura, Al servicio de la historia. Bosquejo histórico de la Dictaduratomo 2 (Madrid: Javier Morata Editor, 1930) pp. 71-2; Perucho, Catalunya sota la dictadura, note by Josep Palomero, pp. 308-9; Pérez, Notas oficiosas, pp. 272-3.

[14]‘Van saliendo los chanchullos’, Hojas Libres, No.6, 1 September 1927, pp. 82-4;Salazar Alonso, La justicia, pp. 177-84; López Ochoa, De la Dictadura a la República, pp. 69-70; Pedro María Velarde & Fermín Allende Portillo, ‘Un año selectivo para la banca en Bilbao’, in Pablo Martín Aceña & Montserrat Gárate Ojanguren, editors, Economía y empresa en el norte de España (Una aproximación histórica) (Bilbao: Universidad del País Vasco, 1994) pp. 171-4.

[15]‘La Inmoralidad de la Dictadura’, Hojas Libres, No.15, June 1927, pp. 70-1; ‘El homenaje bochornoso al Dictador’, Hojas Libres, No.11, February 1928, pp. 74-81; ‘La casa del homenaje y el Código Penal’, Hojas Libres, No.12, March 1928, pp. 65-6..

[16] Francisco Hernández Mir, La Dictadura ante la Historia: un crimen de lesa patria (Madrid: Compañía Ibero-Americana de Publicaciones, 1930) pp. 245-58; ABC, 9 March 1929.

[17] ABC, 29 September 1929.

[18] Pérez, Notas oficiosas, pp. 270-2; ‘Los últimos chanchullos’, Hojas Libres, No.12, March 1928, p. 62.

[2]‘Algunas sinecuras de los renovadores’, Hojas Libres, No.7, 1 October 1927, pp. 75-8.

[3] Calvo Sotelo, Mis servicios, p. 332.

[4]‘Relación de chanchullos de la Dictadura (continuación)’,Hojas Libres, No.8, 1 November 1927, pp. 7-10.

[5]‘La Inmoralidad de la Dictadura’, Hojas Libres, No.15, June 1927, pp. 65-70; Maura, Bosquejo, I, p. 345; López Ochoa, De la Dictadura a la República, p. 161; Ben-Ami, Fascism from Above, pp. 245-6.

[6] José Luis Gómez Navarro, El régimen de Primo de Rivera (Madrid: Ediciones Cátedra, 1991) p. 170; Jaume Muñoz Jofre, La España corrupta. Breve historia de la corrupción (de la Restauración a nuestros días, 1976-2016) (Granada: Comares, 2016) p. 47.

[7]‘La torva historia de Anido’, Hojas Libres, No.2, 1 May 1927, pp. 81-6.

[8]‘Los últimos chanchullos’, Hojas Libres, No.12, March 1928, pp. 59-61.

[9] Saldaña, Al servicio de la justicia, pp. 169-76;

[10] Calvo Sotelo, Mis servicios, pp. 194-203; ‘Grandes negocios. El monopolio petrolífero’, Hojas Libres, No.4, 1 July 1927, pp. 74-6; ‘Primo y sus amigos. Estafa de más de dos millones de pesetas’, Hojas Libres, No.9, December 1927, pp. 24-5; Ben-Ami, Fascism from Above, pp. 248-50; Ramón Tamames, Ni Mussolini ni Franco: la dictadura de Primo de Rivera y su tiempo (Barcelona: Planeta, 2008) pp. 329-331.

[11]‘La Dictadura de Monipodio’, Hojas Libres, No.9, December 1927, pp. 45-8; Artur Perucho i Badia, Catalunya sota la dictadura (Barcelona: Publicacions de l’Abadia de Montserrat, 2018) pp. 308-10.

[12]‘Primo y sus amigos’, Hojas Libres, No.9, December 1927, pp. 24-9.

[13] Miguel de Unamuno, ‘Democracia y cleptocracia’, Hojas Libres, No.19, 1 January 1929;Gabriel Maura, Al servicio de la historia. Bosquejo histórico de la Dictaduratomo 2 (Madrid: Javier Morata Editor, 1930) pp. 71-2; Perucho, Catalunya sota la dictadura, note by Josep Palomero, pp. 308-9; Pérez, Notas oficiosas, pp. 272-3.

[14]‘Van saliendo los chanchullos’, Hojas Libres, No.6, 1 September 1927, pp. 82-4;Salazar Alonso, La justicia, pp. 177-84; López Ochoa, De la Dictadura a la República, pp. 69-70; Pedro María Velarde & Fermín Allende Portillo, ‘Un año selectivo para la banca en Bilbao’, in Pablo Martín Aceña & Montserrat Gárate Ojanguren, editors, Economía y empresa en el norte de España (Una aproximación histórica) (Bilbao: Universidad del País Vasco, 1994) pp. 171-4.

[15]‘La Inmoralidad de la Dictadura’, Hojas Libres, No.15, June 1927, pp. 70-1; ‘El homenaje bochornoso al Dictador’, Hojas Libres, No.11, February 1928, pp. 74-81; ‘La casa del homenaje y el Código Penal’, Hojas Libres, No.12, March 1928, pp. 65-6..

[16] Francisco Hernández Mir, La Dictadura ante la Historia: un crimen de lesa patria (Madrid: Compañía Ibero-Americana de Publicaciones, 1930) pp. 245-58; ABC, 9 March 1929.

[17] ABC, 29 September 1929.

[18] Pérez, Notas oficiosas, pp. 270-2; ‘Los últimos chanchullos’, Hojas Libres, No.12, March 1928, p. 62.

These images have been chosen by De Re Histographica to illustrate the text by Paul Preston

No comments:

Post a Comment