As dictator, Franco built a cemetery with slave labour and orphanages for his murdered enemies’ children. Then Spain discovered tourism – and the lager louts flew inJonathan Meades

Polished diamond … Miguel Fisac’s Pagoda, outside Madrid, which was demolished in 1999.

The Basilica at Arantzazu in the Basque country was a collaboration between the sculptor

Jorge Oteiza, who had just returned to Spain after 15 years in self-imposed exile, and the architect

Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oiza (who would become celebrated for his Torres Blancos building in Madrid). Though they won the competition for the building in 1949, it was not consecrated until 1959, after a disputatious decade of ecclesiastical factionalism and local objections. The latter were preposterous given the building’s remoteness at the end of a vertiginous mountain road.

The Basilica is the earliest of several Spanish churches whose novel dispositions of space anticipated and influenced the liturgical changes that would be stipulated by the second

Vatican council in 1962. The exterior is tough, fortified, uncompromising. Its break from the conventions of sacred design was a papal snub to Franco, a reminder that his power was merely temporal.

Luis Buñuel was the greatest Spanish artist of the 20th century. He believed that Picasso’s

Guernica was a meretricious work that should be burned and that mortadella was made by the blind. St James, whom Franco would restore to the position of patron of Spain from which he had been ignominiously removed by the Republic, encountered the Virgin while praying on the banks of the Ebro at Caesaraugusta, later Zaragoza. She was held aloft on a jasper pillar born by angels, hence the name of Zaragoza’s basilica, El Pilar.

She set a precedent for attention-craving ascetics such as St Simeon Stylites, who lived for 37 years on top of a pillar near Aleppo and was the subject of Buñuel’s

Simon of the Desert. Buñuel was the most devout, most observant, most gleefully blasphemous of atheists. After more than 20 years in exile, during which he became a Mexican citizen, he returned to Spain to make

Viridiana: all necrophilia, incest and

Fernando Rey. Because no one was looking and Buñuel was cunning, it was chosen as Spain’s entry at the 1961 Cannes film festival. Given the Franquist state’s zealous censorship of writers and film-makers, this was an extraordinary lapse. It won the Palme d’Or. All hell broke loose. It was denounced by the Vatican. Its production companies were closed down. Buñuel once again became persona non grata. Viridiana would not be shown in Spain until 1979, four years after the death of Franco – but not of Franquismo. Over 40 years on it’s still loitering, a grubby menacing sideshow.

Equally extraordinary was the state’s habitual tolerance of nearly all forms of art and architecture. Like many dictators Franco considered himself an artist. He brought shame to Sunday painters. He dismissed as derisory the abstraction that was pervasive from the late 40s till the mid 60s. He rightly considered it politically and socially impotent. It wasn’t Goya, it wasn’t

Otto Dix. It was harmless, self-referential pattern-making that, while it might provoke strong feelings about aesthetic legitimacy, was not going to fire up insurrection. And the various strains of architecture that asserted themselves over an even longer period were, like all architecture down the ages, near mute. Architecture is not a language. It does no more than grunt generalisations: “looking forward” or “summoning the past” or “aiming for the heavens”.

Franco was described by Churchill as “a gallant Christian gentleman”. HG Wells corrected him: “a murderous Christian gentleman”. From an early age the future murderer unquestioningly accepted the Christian dogma he was force-fed at school in the Galician port of Ferrol – which was also an arsenal and a garrison. He accepted too a garrison’s hierarchy as the natural order: martial discipline, martial asceticism and martial mores. Add to those an oppressive, omnipresent religious credulousness that infected all aspects of life. Franco believed his destiny was to become the equal of the omnipotent imperial Hapsburg King Philip II. He also sought somehow to reincarnate the medieval military hero

El Cid. When

the dreary film with gun-crazy Charlton Heston in the title role was shot near Valencia, Franco loaned the production several thousand soldiers as extras – which no doubt helped with his metempsychotic ambition.

Papal snub … the Basicilia at Arantzazu. Photograph: Ainara Garcia/Alamy Stock Photo

Two buildings were deemed to be the pinnacle of Spanish architectural achievement. The

Escorial was holy as well as regal.

Juan de Herrera was commanded by Philip II to make a building that expressed nobility without arrogance, majesty without ostentation – rather like Polonius telling Laertes how to dress. Herrera was also responsible for the

Alcázar of Toledo. Their obsessive and repetitive sobriety is, weirdly, as dizzying as the overwrought freneticism of the baroque or

churrigueresque. And, just as weirdly, their chilly rigour feels protestant. They provided the model for Franco’s essays in “state architecture”, among them:

The

Valle de los Caídos (Valley of the Fallen), the monumental act of hypocrisy in stone where he is buried. This was the biggest slave labour project in Europe since the second world war. The slaves were captured republicans, political prisoners, housed in a concentration camp and worked to death with the assurance that “el trabajo enoblece”. Whose German translation is “

arbeit macht frei”.

The

air ministry in Madrid. The disjunction of style and purpose again suggests architectural insentience, as though planes belonged to the 16th century.

The

University of Gijón by Luis Moya is the largest building in Spain. It was originally intended as an orphanage but soon became a technical school too. Franco created orphans by the thousand. Like

Goya’s Chronos, he ate them by the score.

He built orphanages; more like madrassas really. Indoctrination with lashings – take that how you will – of orthodoxy and obscurantism. The children of murdered republicans would be brainwashed with mariology and hagiology. Their heretical names would be changed from the revolutionary names their dead parents had given them: Passionaria, Luxemburg, Prairial, Germinal, Danton, St Just. Their teachers were brides and bridegrooms of Christ, the rank and paedophile of the Catholic church who enjoyed job satisfaction.

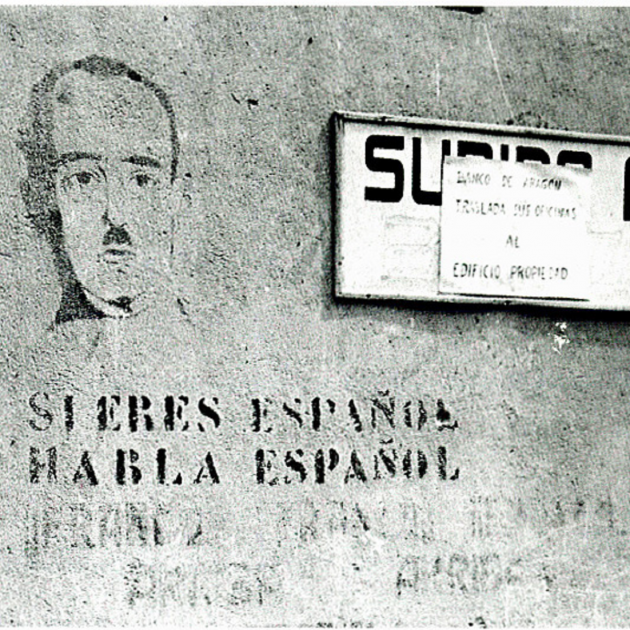

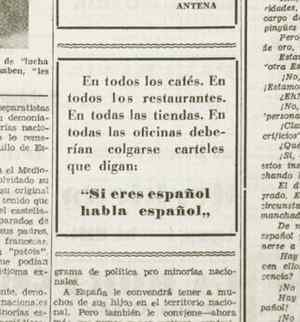

Though Gijón is in the Asturias, the building’s distended classicism has nothing to do with the architecture of that province. It is rather an emblem of Franco’s moral reconquest, his sacralisation of everyday life, his castillianisation of everyday life, his unification. Provinces that didn’t fall into line were likely to suffer aerial diplomacy.

Moya’s Gijón University building.

This phase of official architecture didn’t last. The civil war and Franco’s collaboration seemed to get lost in a fog of international amnesia. This amnesia was encouraged by America’s strategic friendship of convenience: financial assistance in return for land on which to build airbases. Ideology could be suspended in exchange for white goods, jukeboxes, two-tone cars.

The government was increasingly influenced by the lay Catholic organisation Opus Dei and its so-called technocrats, judicious pragmatists determined to open Spain to the world beyond the Pyrenees known as the continent. The architectural work of the Opus Dei member

Miguel Fisac was part of that process. Spain was trying to achieve what would be internationally recognised as a sort of normality: fascism was, by the mid 1950s, a freakish outlier from a past that was to be ignominiously buried, along with its victims. The appetite for recrimination was frail.

One of the few things buildings can articulate is newness, a prospect of a progressive future.

Fisac’s quite wonderful Pagoda, which anyone arriving at Madrid airport and driving into the city could not help but see, was an unequivocal message that Spain had caught up at last, it was modern. And the modern state vandalises. This great building was demolished three decades after it was built.

Infrastructure tends to endure more. Land colonies in the form of new villages were built in the 1950s and 60s under the direction of the agromomist Rafael Cavestany. The government feared a recurrence of the second republic’s food shortages and consequent public disorder unless something was done to tackle the inequity of land ownership. Agrarian reform would not only bring improved crops and improved livestock, it would transform still feudal peasants into sort of proper smallholders. The chaos of land ownership would be resolved. And the rural diaspora would be reversed. The villages invite correspondences with Nazi settlement programmes but the latter were more trumpeted than delivered, and where they were achieved they were folksy, wilful expressions of blood and soil.

Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oiza’s Torres Blancas building in Madrid. Photograph: Martin Thomas Photography/Alamy Stock Photo

Thirty thousand houses were built in settlements of diverse sizes, many in areas that had till lately been arid. Franco boasted that his greatest legacy to the country he had otherwise despoiled was his irrigation of it. He built more than 500 dams. He liked to preside at their openings, quite ignoring how ecologically disastrous many of them were.

His self-esteem swelled, a goitre of patriotic pride. Changing the climate – whether by cloud seeding or diverting rivers – is the mark of a human god, an aquarian magician who was described as a statesman unique in the world, laying the hydraulic foundations for the wellbeing and progress of his people.

Bad geography meant too much rain in the north, too little in the south. Surfeit and deficit: with deficit came drought. The most grandiose of the schemes to overcome the natural imbalance was the

Tajo Segura Transfer.

Water is pumped to a height of 300 metres above the dammed Tajo in the mountains east of Madrid. Canalised, it flows 300km through a system of reservoirs, dams, tunnels, pumping stations and aqueducts to Murcia, the region of

Spain most frequently afflicted by drought and the one that supplied Franco’s Nationalists with its most murderous butchers.

It is anyway a great feat of hydraulic engineering. Whose beneficiaries were the latifundistas, the landowners who had backed Franco. And whose favourite sport was jocularly called agrarian reform. It consisted of hunting on horseback with packs of dogs. The quarry comprised destitute peasants, rural reds, bucolic bolshies.

They were people who didn’t have a ladder to be at the bottom of – and whose body would be dumped in the usual pit. The other losers were the thousands of inhabitants of villages drowned because they stood in the way of reservoirs. Many of the interventions were also ecologically disastrous: in the age-old battle between environment and profit – here posing as the common good and agrarian reform – it was profit that won. The bottom line is the most potent of ideals.

In 1948

Santiago de Compostela attracted half a million pilgrims … or tourists. They enjoyed such pious diversions as fireworks, football tournaments and bullfights, even though the last were not, and are still not, locally popular. It was – still is – the least Españolada province of Spain, that is the least afflicted by castanets, bells, bulls and balls and all the Hemingway/

Tynan nobility-of-machismo schtick.

But the jamboree was not merely a question of devotion to St James, or of penitence, of absolution, of self-denial. It was an earner. Here was an opportunity for the pariah state, denied foreign aid, to get its fascist gauntlets on some democratic coin: sovs, krone, francs. The germ of an idea was planted.

Money over morality … Levante Beach, Benidorm. Photograph: David Ramos/Getty Images

Pedro Zaragoza was an energetic Franquist placeman born in the small, economically straitened fishing port between Valencia and Alicante. He was sent back there from Madrid to be its mayor at the age of 28.

Zaragoza would become one of the most effective urbanists in the world. Not least because he had probably never heard of the pseudoscience of urbanism, had never shown interest in theories that fell off the back of a lorry loaded with dogmatic pretention. He turned an off-the-map village into an enterprise that changed a nation. When he took up his post in 1950, Benidorm had four hotels – hostels really – which provided fewer than 100 beds.

“Render unto Caesar the things which be Caesar’s and unto God the things which be God’s.” Together with Jesus’s retort to Pilate that “my kingdom is not of this world”, this may be read as a way of emphasising that the temporal state and the sacred church are separate. So while God-botherers may have indignantly objected to displays of flesh, to displays of public drunkenness, to displays of mob loutishness by Ingerlandlandland’s finest, their opinion counted for little. Impious money will always take precedence over prim morality. Throwing the merchants out of the temple was the work of a prig.

Police were instructed to turn a blind eye, which, given what they would be having to look at, was probably what they wanted anyway – though when they did intervene it was with batons, firearms, chains and daft hats. That’s just good old-fashioned coppering, Spanish style.

Franco hugely approved of the place. Forget the provenance. It’s no more wicked than a Volkswagen car. And it’s an architectural marvel where on any given night you can hear one of the 17 bands that claim to be the authentic Rubettes damaging their throats.

Franco Building by Jonathan Meades is on BBC Four at 10pm on 27 August.

Ascensión Mendieta, hija de Timoteo | EFE

Ascensión Mendieta, hija de Timoteo | EFE