Every nationalist wants to be free of a bigger administration they see as bad. But not everyone who wants to be free of a bad administration is a nationalist. Getting this logic wrong, proves that one is making propaganda, like #Spain and the #EU do against #Catalonia. https://t.co/pcQgos1DRM— Quantum (@QuantumAspect) August 7, 2019

2010: The unfairness of the construction of Spain as Nation, since its early Catholic inception till its latest Fascist design, and its maintenance as a fiction of unity that does not exist and will never do, has cost the different territoires under its flag too much suffering. Spain as a concept is a failure and is still a place to be explained and to be redeemed from its pain.This is a place for memory recovered, for causes to be revised and for traumas to be processed.

Wednesday, 31 July 2019

clarificaciones muy importantes sobre los límites de las narrativas tóxicas contra Cataluña

Tuesday, 30 July 2019

Spain’s Dictator Is Dead, but the Debate About Him Lives On

Francisco Franco ran Spain with an iron fist for decades—and created myths about his rule that are only now starting to come undone.

BY OMAR G. ENCARNACIÓN | JULY 27, 2018, 12:02 PM

People make the fascist salute at La Basilica The Valley of Fallen in San Lorenzo del Escorial near Madrid on July 15, 2018, as they protest against the removal of Franco's remains from The Valley of Fallen. (JAVIER SORIANO / AFP)

Last month, within days of taking office, Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez announced his government’s intention to exhume the remains of Francisco Franco, the strongman who ruled Spain from the end of the Spanish Civil War in 1939 until his death of natural causes in 1975. Expected to take place before the end of the summer, the exhumation plan calls for transferring Franco’s remains to a location yet to be determined. Just as controversial is Sánchez’s proposal to transform the remains’ current resting place, the Valle de los Caídos (the Valley of the Fallen), into a memorial for the victims of the Civil War and Franco’s dictatorship.

El Valle, one of Europe’s largest and most imposing public monuments (the entire complex, often derided for its fascist theatricality, includes a basilica, a Benedictine abbey, and a cross rising some 500 feet that is visible from over 30 miles away), was inaugurated by Franco himself in 1959 to mark the 20th anniversary of his victory in the Civil War. Virtually untouched since Franco’s embalmed body was interred there, the monument is a veritable shrine to Francoism and an obligatory pilgrimage for Franco’s defenders. In recent weeks, the most devout of these defenders have taken to the streets of Madrid chanting, “El Valle no se toca” (Don’t touch the valley).

To outside observers, the news of Franco’s exhumation and the controversy around it give rise to obvious questions: Why was Franco spared the popular infamy at home accorded to fellow fascist leaders Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini? And why is the status quo about how Franco has been memorialized since his death getting upended now? Answering these questions requires delving into the peculiarities of how Spain became a democracy in the late 1970s and the unusual choices about the country’s dark and painful history made by the politicians and the public as part of the democratic transition.

Much about Franco’s fate, both materially and figuratively, in the period after his death is due to the fact that the transition to democracy in Spain left very little room for justice and accountability toward the old regime. Unlike its sister dictatorship in Portugal—the António de Oliveira Salazar regime—which was uprooted by a popular uprising, the Franco regime was reinvented from the inside out as a democracy by a process of political reform spearheaded by a young King Juan Carlos. Although the king had promised Franco to carry on with “Francoism without Franco,” after the death of the dictator—and responding to the popular clamoring for democracy—he went back on his word and put Spain on the path to democracy by calling for free elections in 1977.

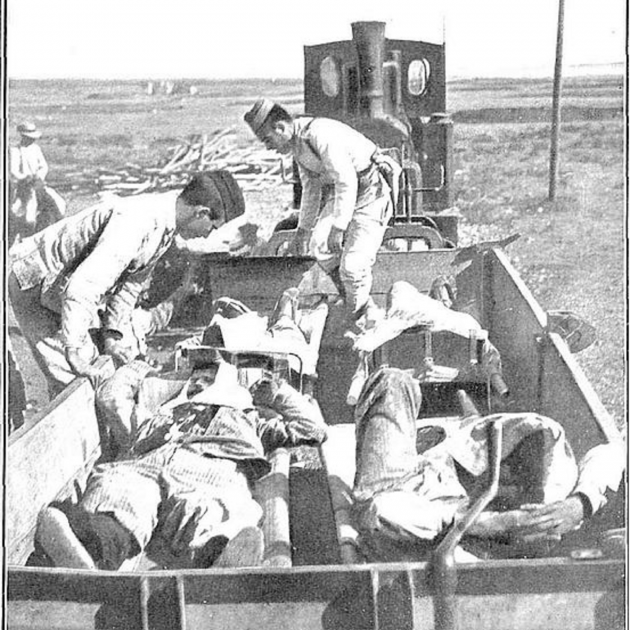

The democratic reinvention of the Franco regime meant that the losing side of the Civil War—the Republicans, a mostly leftist coalition of liberals, communists, socialists, and anarchists that resisted Franco’s assault on the popularly elected Second Republic—never got the chance to make Franco pay for his political sins. In what historians have referred to as the “Spanish Holocaust,” as many as 200,000 political dissidents were executed by Franco’s militias; an additional 400,000 were imprisoned in jails and concentration camps established by Franco after the end of the Civil War, where many died of malnutrition and starvation. An unknown number of prisoners were forced into virtual slavery to aid in the postwar reconstruction effort, including building El Valle. Some 500,000 people fled Spain as political refugees.

As part of the political negotiations that allowed for a swift and orderly transition to democracy, politicians from across the ideological spectrum agreed to a “pact of forgetting” that was institutionalized with a broad amnesty law, enacted just before the 1977 elections. This was “amnesty for everyone” as one politician put it, since it included anyone who had ever committed a political offense prior to 1977. Despite bearing the brunt of Franco’s repression, the left was eager to support this pact. It helped conceal the left’s political sins, especially the so-called Red Terror, the wave of killings that left anywhere from 20,000 to 70,000 Francoist supporters dead, including some 2,000 clergy, many of them later beatified by the Pope as Civil War martyrs.

An important reason why the politicians were able to let bygones be bygones was the complicity of the public. At the heart of this complicity is the ambivalence that many Spaniards feel toward the Franco regime. Polling data gathered in 2008 by Madrid’s Center for Sociological Research, a government research center, showed that a majority of the public acknowledged that Franco did “both good and bad things.” This data also showed the public opposed to the prosecution of former Franco officials and lukewarm about a truth commission to assign responsibility for the Civil War. And no national organization demanding accountability against the old regime emerged until the movement for the recovery of the historical memory began to gain steam in the early 2000s.

Spanish society’s complicity in silencing the past did not develop in a vacuum. In the wake of Franco’s death, fears of another civil conflict and another dictatorship were widespread. Less apparent is the intense process of political socialization that the public endured under the dictatorship. The Franco regime encouraged silence about the Civil War, which accounts for why Spaniards who lived through the war have very few recollections of this event being discussed at home, in schools, or in the workplace. After the end of the Civil War, Franco and his allies also began to promote numerous myths about the war and the regime—aided by a vast propaganda machine, including press reports, films and documentaries, and school textbooks—that in the post-transition period have done wonders to discourage any revisiting of the past.

Among the popular myths of the Civil War is that of shared responsibility, which holds both sides of the conflict equally at fault. It conveniently overlooks the fact that in 1936, Franco overthrew a popularly elected government. Another popular myth is “collective madness,” which absurdly theorizes that Spaniards lost their minds and began killing each other for no logical reason. Yet another popular narrative is to blame foreign ideological influences, especially anarchism. In this view, Spain is cast as a victim of outside forces. Nothing, however, trumps the salvation theory, the view that Franco’s uprising in 1936 saved Spain from the chaos and violence of the Second Republic. This outrageously cynical reading of history ignores both the chaos and violence that Franco inflicted on Spain, and that whatever degree of peace Franco was able to bring to the country was purchased with the lives of close to 1 million people.

The salvation theory was boosted by the political stability that Spain enjoyed after 1959—after all those in opposition to Franco had been either killed or forced into exile—and by an economic “miracle” that began to unfold in the early 1960s and lifted millions of Spaniards from abject poverty to the ranks of the middle class. Paradoxically, this very success undermined the salvation theory by blurring the memory of the Civil War and the misery of the postwar years. Thus, by the 1960s, the notion of the Franco dictatorship as a modernizing regime was born, with socioeconomic progress as the regime’s new rationale for its existence. In the post-transition era, this last regime reinvention has allowed Franco’s defenders to claim that the dictatorship paved the way for the successful democracy that Spain is today.

It was not until 2007, with the enacting of the Historical Memory Law by the Socialist administration of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, that the Civil War myths promoted by the Franco regime began to be seriously questioned. The law declared the Franco government illegitimate; called for the removal from public view of public monuments honoring the Franco regime, save for those with historical significance; provided financial compensation to those victimized by the Franco regime; restored Spanish citizenship to the Republican exile community; and created a center for the study of the Civil War in the city of Salamanca. Propelling the law was a new generation of Spaniards curious about the Civil War and no longer traumatized by the memories of the past, including Zapatero, the grandson of a military captain executed by a Francoist brigade for refusing to join the rebellion against the Republican government.

READ MORE

Here’s How to Finally Solve Spain’s Governmental Standstill

A coalition between Pedro Sánchez’s Socialists and Albert Rivera’s Ciudadanos could prevent a fourth election in as many years—but voters are unlikely to buy it.

ARGUMENT | MARK NAYLER

Spain’s Formula to Live Forever

The country is set to boast the world’s longest life expectancy by 2040. What are the Spanish doing right?

ARGUMENT | RAPHAEL MINDER

Pablo Casado Was Meant to Save Spain’s Center-Right. He Destroyed It.

Spain’s conservatives lost more than half their seats in parliament by trying to outbid the far-right.

DISPATCH | RAPHAEL MINDER

Sánchez, another Socialist leader too young to have been affected by the Francoist socialization of Spanish society and to have partaken in the transition, is clearly following in Zapatero’s footsteps. Despite protests by right-wing groups, there is relatively little risk for Sánchez in exhuming Franco’s remains. The conservative opposition Popular Party, which fiercely opposed the 2007 Historical Memory Law, is in disarray, having been unceremoniously ousted from power in June after a no-confidence vote and fighting a challenge from the right by the Ciudadanos party. The Spanish Bishops’ Conference, which has a say over any tinkering with El Valle due to the monument’s status as a religious site, is staying neutral on the exhumation. Franco’s relatives are not objecting, noting that Franco never expressed any desire to be buried at El Valle. Their only disagreement is what to do with the remains.

Most important, 56 percent of the public is in favor of the exhumation. This signals how much further along the public is on the issue of the past than when the 2007 Historical Memory Law was enacted. At that time, 52 percent of the public thought it best to leave Franco’s remains undisturbed. This shift in public opinion reflects, in no small measure, the success of the memory law in breaking the taboo of legislating the memory of the Civil War and in making the public more aware about the human rights abuses of the old regime. In 2011, Spain was shaken by allegations that under Franco some 300,000 babies were stolen from “undesirable” parents and sold to “approved” families. Operated by a sinister network of nuns, priests, and doctors, the trafficking began in the 1930s to “save” the babies from their “red” parents, but it later grew to include “morally deficient parents.” It lasted into the 1980s, when adoption laws were revised.

Not surprisingly, many see political calculation in Sánchez’s decision to exhume Franco, including a bid to improve his reelection chances by energizing left-wing voters. Indeed, the exhumation fits well within Sánchez’s strategy of recasting Spain as a modern, forward-looking, liberal state. This recasting is a not-too-thinly veiled appeal to progressive voters nationwide, but especially in the restive region of Catalonia, where the claim that Spain (and the central administration in Madrid in particular) is backward-looking and wedded to the past has been a rallying cry in the region’s drive for independence.

But whether an act of political opportunism or not, moving Franco’s remains out of El Valle would be one of most consequential decisions made by any Spanish premier in the post-Franco era. Aside from allowing for the creation of an appropriate memorial to the victims of the Civil War, the exhumation would clear the way for many of the things that the international human rights community, including the United Nations’ Committee on Enforced Disappearances, has for years been demanding from Spain, especially state support for the exhumation and proper burial of those in thousands of Civil War-era mass graves found all over the Spanish territory—the majority of them Republican. Ironically, it is the political stability created by the silencing of the past after Franco’s death that today allows Spain to undertake these painful tasks.

Omar G. Encarnación is a professor of political studies at Bard College and author of Out in the Periphery: Latin America's Gay Rights Revolution.

BY OMAR G. ENCARNACIÓN | JULY 27, 2018, 12:02 PM

People make the fascist salute at La Basilica The Valley of Fallen in San Lorenzo del Escorial near Madrid on July 15, 2018, as they protest against the removal of Franco's remains from The Valley of Fallen. (JAVIER SORIANO / AFP)

Last month, within days of taking office, Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez announced his government’s intention to exhume the remains of Francisco Franco, the strongman who ruled Spain from the end of the Spanish Civil War in 1939 until his death of natural causes in 1975. Expected to take place before the end of the summer, the exhumation plan calls for transferring Franco’s remains to a location yet to be determined. Just as controversial is Sánchez’s proposal to transform the remains’ current resting place, the Valle de los Caídos (the Valley of the Fallen), into a memorial for the victims of the Civil War and Franco’s dictatorship.

El Valle, one of Europe’s largest and most imposing public monuments (the entire complex, often derided for its fascist theatricality, includes a basilica, a Benedictine abbey, and a cross rising some 500 feet that is visible from over 30 miles away), was inaugurated by Franco himself in 1959 to mark the 20th anniversary of his victory in the Civil War. Virtually untouched since Franco’s embalmed body was interred there, the monument is a veritable shrine to Francoism and an obligatory pilgrimage for Franco’s defenders. In recent weeks, the most devout of these defenders have taken to the streets of Madrid chanting, “El Valle no se toca” (Don’t touch the valley).

To outside observers, the news of Franco’s exhumation and the controversy around it give rise to obvious questions: Why was Franco spared the popular infamy at home accorded to fellow fascist leaders Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini? And why is the status quo about how Franco has been memorialized since his death getting upended now? Answering these questions requires delving into the peculiarities of how Spain became a democracy in the late 1970s and the unusual choices about the country’s dark and painful history made by the politicians and the public as part of the democratic transition.

Much about Franco’s fate, both materially and figuratively, in the period after his death is due to the fact that the transition to democracy in Spain left very little room for justice and accountability toward the old regime. Unlike its sister dictatorship in Portugal—the António de Oliveira Salazar regime—which was uprooted by a popular uprising, the Franco regime was reinvented from the inside out as a democracy by a process of political reform spearheaded by a young King Juan Carlos. Although the king had promised Franco to carry on with “Francoism without Franco,” after the death of the dictator—and responding to the popular clamoring for democracy—he went back on his word and put Spain on the path to democracy by calling for free elections in 1977.

The democratic reinvention of the Franco regime meant that the losing side of the Civil War—the Republicans, a mostly leftist coalition of liberals, communists, socialists, and anarchists that resisted Franco’s assault on the popularly elected Second Republic—never got the chance to make Franco pay for his political sins. In what historians have referred to as the “Spanish Holocaust,” as many as 200,000 political dissidents were executed by Franco’s militias; an additional 400,000 were imprisoned in jails and concentration camps established by Franco after the end of the Civil War, where many died of malnutrition and starvation. An unknown number of prisoners were forced into virtual slavery to aid in the postwar reconstruction effort, including building El Valle. Some 500,000 people fled Spain as political refugees.

As part of the political negotiations that allowed for a swift and orderly transition to democracy, politicians from across the ideological spectrum agreed to a “pact of forgetting” that was institutionalized with a broad amnesty law, enacted just before the 1977 elections. This was “amnesty for everyone” as one politician put it, since it included anyone who had ever committed a political offense prior to 1977. Despite bearing the brunt of Franco’s repression, the left was eager to support this pact. It helped conceal the left’s political sins, especially the so-called Red Terror, the wave of killings that left anywhere from 20,000 to 70,000 Francoist supporters dead, including some 2,000 clergy, many of them later beatified by the Pope as Civil War martyrs.

An important reason why the politicians were able to let bygones be bygones was the complicity of the public. At the heart of this complicity is the ambivalence that many Spaniards feel toward the Franco regime. Polling data gathered in 2008 by Madrid’s Center for Sociological Research, a government research center, showed that a majority of the public acknowledged that Franco did “both good and bad things.” This data also showed the public opposed to the prosecution of former Franco officials and lukewarm about a truth commission to assign responsibility for the Civil War. And no national organization demanding accountability against the old regime emerged until the movement for the recovery of the historical memory began to gain steam in the early 2000s.

Spanish society’s complicity in silencing the past did not develop in a vacuum. In the wake of Franco’s death, fears of another civil conflict and another dictatorship were widespread. Less apparent is the intense process of political socialization that the public endured under the dictatorship. The Franco regime encouraged silence about the Civil War, which accounts for why Spaniards who lived through the war have very few recollections of this event being discussed at home, in schools, or in the workplace. After the end of the Civil War, Franco and his allies also began to promote numerous myths about the war and the regime—aided by a vast propaganda machine, including press reports, films and documentaries, and school textbooks—that in the post-transition period have done wonders to discourage any revisiting of the past.

Among the popular myths of the Civil War is that of shared responsibility, which holds both sides of the conflict equally at fault. It conveniently overlooks the fact that in 1936, Franco overthrew a popularly elected government. Another popular myth is “collective madness,” which absurdly theorizes that Spaniards lost their minds and began killing each other for no logical reason. Yet another popular narrative is to blame foreign ideological influences, especially anarchism. In this view, Spain is cast as a victim of outside forces. Nothing, however, trumps the salvation theory, the view that Franco’s uprising in 1936 saved Spain from the chaos and violence of the Second Republic. This outrageously cynical reading of history ignores both the chaos and violence that Franco inflicted on Spain, and that whatever degree of peace Franco was able to bring to the country was purchased with the lives of close to 1 million people.

The salvation theory was boosted by the political stability that Spain enjoyed after 1959—after all those in opposition to Franco had been either killed or forced into exile—and by an economic “miracle” that began to unfold in the early 1960s and lifted millions of Spaniards from abject poverty to the ranks of the middle class. Paradoxically, this very success undermined the salvation theory by blurring the memory of the Civil War and the misery of the postwar years. Thus, by the 1960s, the notion of the Franco dictatorship as a modernizing regime was born, with socioeconomic progress as the regime’s new rationale for its existence. In the post-transition era, this last regime reinvention has allowed Franco’s defenders to claim that the dictatorship paved the way for the successful democracy that Spain is today.

It was not until 2007, with the enacting of the Historical Memory Law by the Socialist administration of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, that the Civil War myths promoted by the Franco regime began to be seriously questioned. The law declared the Franco government illegitimate; called for the removal from public view of public monuments honoring the Franco regime, save for those with historical significance; provided financial compensation to those victimized by the Franco regime; restored Spanish citizenship to the Republican exile community; and created a center for the study of the Civil War in the city of Salamanca. Propelling the law was a new generation of Spaniards curious about the Civil War and no longer traumatized by the memories of the past, including Zapatero, the grandson of a military captain executed by a Francoist brigade for refusing to join the rebellion against the Republican government.

READ MORE

Here’s How to Finally Solve Spain’s Governmental Standstill

A coalition between Pedro Sánchez’s Socialists and Albert Rivera’s Ciudadanos could prevent a fourth election in as many years—but voters are unlikely to buy it.

ARGUMENT | MARK NAYLER

Spain’s Formula to Live Forever

The country is set to boast the world’s longest life expectancy by 2040. What are the Spanish doing right?

ARGUMENT | RAPHAEL MINDER

Pablo Casado Was Meant to Save Spain’s Center-Right. He Destroyed It.

Spain’s conservatives lost more than half their seats in parliament by trying to outbid the far-right.

DISPATCH | RAPHAEL MINDER

Sánchez, another Socialist leader too young to have been affected by the Francoist socialization of Spanish society and to have partaken in the transition, is clearly following in Zapatero’s footsteps. Despite protests by right-wing groups, there is relatively little risk for Sánchez in exhuming Franco’s remains. The conservative opposition Popular Party, which fiercely opposed the 2007 Historical Memory Law, is in disarray, having been unceremoniously ousted from power in June after a no-confidence vote and fighting a challenge from the right by the Ciudadanos party. The Spanish Bishops’ Conference, which has a say over any tinkering with El Valle due to the monument’s status as a religious site, is staying neutral on the exhumation. Franco’s relatives are not objecting, noting that Franco never expressed any desire to be buried at El Valle. Their only disagreement is what to do with the remains.

Most important, 56 percent of the public is in favor of the exhumation. This signals how much further along the public is on the issue of the past than when the 2007 Historical Memory Law was enacted. At that time, 52 percent of the public thought it best to leave Franco’s remains undisturbed. This shift in public opinion reflects, in no small measure, the success of the memory law in breaking the taboo of legislating the memory of the Civil War and in making the public more aware about the human rights abuses of the old regime. In 2011, Spain was shaken by allegations that under Franco some 300,000 babies were stolen from “undesirable” parents and sold to “approved” families. Operated by a sinister network of nuns, priests, and doctors, the trafficking began in the 1930s to “save” the babies from their “red” parents, but it later grew to include “morally deficient parents.” It lasted into the 1980s, when adoption laws were revised.

Not surprisingly, many see political calculation in Sánchez’s decision to exhume Franco, including a bid to improve his reelection chances by energizing left-wing voters. Indeed, the exhumation fits well within Sánchez’s strategy of recasting Spain as a modern, forward-looking, liberal state. This recasting is a not-too-thinly veiled appeal to progressive voters nationwide, but especially in the restive region of Catalonia, where the claim that Spain (and the central administration in Madrid in particular) is backward-looking and wedded to the past has been a rallying cry in the region’s drive for independence.

But whether an act of political opportunism or not, moving Franco’s remains out of El Valle would be one of most consequential decisions made by any Spanish premier in the post-Franco era. Aside from allowing for the creation of an appropriate memorial to the victims of the Civil War, the exhumation would clear the way for many of the things that the international human rights community, including the United Nations’ Committee on Enforced Disappearances, has for years been demanding from Spain, especially state support for the exhumation and proper burial of those in thousands of Civil War-era mass graves found all over the Spanish territory—the majority of them Republican. Ironically, it is the political stability created by the silencing of the past after Franco’s death that today allows Spain to undertake these painful tasks.

Omar G. Encarnación is a professor of political studies at Bard College and author of Out in the Periphery: Latin America's Gay Rights Revolution.

Tuesday, 23 July 2019

The New York Times: The Former Police Commissioner Rattling Spain’s Establishment

Image José Manuel Villarejo, a former Spanish police commissioner now at the heart of 10 investigations, arriving at court in Madrid in 2016.CreditCreditEFE, via Shutterstock

By Raphael Minder

July 29, 2019

Leer en español

MADRID — Over more than 20 years as a Spanish police commissioner, José Manuel Villarejo rubbed shoulders with politicians, judges, journalists, aristocrats and business leaders. He was decorated six times, including for helping Spain fight terrorists. Still, he was a relatively unknown figure to the Spanish public.

All of that changed 20 months ago, after he was arrested.

Today the onetime police hero sits at the center of a tangle of 10 investigations by Spanish prosecutors. They accuse him of having worked an illicit and lucrative sideline for years as a secret fixer for Spain’s rich and powerful, who they say used his services to spy on their rivals and smear their enemies.

With his trim white beard, dark glasses and cap, Mr. Villarejo, 67, is now one of Spain’s most recognized faces. But it is his voice that has sent shock waves through nearly every part of the Spanish establishment.

Mr. Villarejo secretly recorded his numerous dealings. Even as he sits in jail, snippets of those conversations are surfacing in the Spanish news media. The leaks have made it clear that the retired police commissioner may well have dirt on just about everyone who is anyone among Spain’s political and business elite.

“He recorded absolutely everything — all his phone calls and meetings — so we know that it’s a huge archive,” said Joaquín Vidal, the director of moncloa.com, an online publication that has released several of Mr. Villarejo’s recordings without explaining exactly how it got them.

“He was somehow allowed to operate from the shadows while becoming a front-line actor in some of the key events of the recent history of Spain,” Mr. Vidal said.

Unlock more free articles.Create an account or log in

The recordings, combined with Mr. Villarejo’s court testimony, have opened a window onto a world of dirty tricks at the top reaches of power in Spain. They have spawned numerous investigations, including whether Spain’s former conservative government used a special “patriotic police” — a secretive unit working for the Interior Ministry — to tarnish political opponents.

Mr. Villarejo learned his way around the underworld while stationed in the Basque region, as part of an antiterrorism unit responsible for dismantling the separatist group ETA, for which he received his first medal in the 1970s.

He then spent a decade on leave from the police, dedicating himself to unspecified business activities, before rejoining the police in Madrid in the 1990s and resuming his rise up the ranks. But his undercover work also stretched far beyond Spain.

His career began to unravel in 2016 after investigators stumbled across millions of euros that they say Mr. Villarejo had hidden offshore.

Among their discoveries, prosecutors say, Mr. Villarejo was paid 5.3 million euros (about $5.9 million) from the government of President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo — who has been in power in Equatorial Guinea, a former Spanish colony, since 1979 — to help the African leader tarnish his political opponents.

Justice Minister Dolores Delgado, front left, receiving support from other Socialists in Parliament last September, after she said she was a target of “political blackmail” using one of Mr. Villarejo’s recordings.CreditFernando Villar/EPA, via Shutterstock

Justice Minister Dolores Delgado, front left, receiving support from other Socialists in Parliament last September, after she said she was a target of “political blackmail” using one of Mr. Villarejo’s recordings.CreditFernando Villar/EPA, via ShutterstockSince Mr. Villarejo’s arrest, judges have frozen millions of euros’ worth of assets controlled by companies that he and associates used to buy properties in Spain, as well as a hotel in Punta del Este, Uruguay’s fashionable beach resort.

Today, prosecutors are pursuing charges against him, including bribery and money laundering. About 50 other people, including some other police chiefs, have also been indicted in the sprawling series of investigations.

Mr. Villarejo denies the accusations and says his companies were set up as part of his undercover work, mandated by the highest levels of government.

In fact, he says he carried out his work on behalf of the Spanish state. He has portrayed himself as a loyal soldier of the Spanish government, its police and even its secret service, which he says has now jettisoned and betrayed him.

“There has been an attempt to demonize him as the public enemy No. 1 when it is exactly the opposite,” Mr. Villarejo’s lawyer, Antonio José García Cabrera, told reporters in January.

“Mr. Villarejo forms part of the state structure, he has helped political parties and governments in the missions that he was assigned as an undercover agent,” the lawyer said. “If things have to come out, then everything should come out and be made public.”

That defense has deepened questions of whether parts of the Spanish state and government improperly deployed members of the police and security services to smear and attack opponents.

“This is a very serious scandal,” said Diego Muro, a Spanish lecturer at the University of St Andrews in Scotland.

The big question, he said, is whether Mr. Villarejo’s activities provide “proof that there is a ‘deep state’ that governs in the shadows.’’

In a television interview shortly before entering jail, Mr. Villarejo said that he was ready to disclose his secrets “before I suffer a traffic accident.” At the time of his arrest, the police and prosecutors say, they confiscated about 20 terabytes of encrypted material from Mr. Villarejo’s computers.

It is not clear who leaked the recordings. But their authenticity has not been challenged — the people recorded by Mr. Villarejo have only denied wrongdoing, rather than talking to him. Many are paying a price already.

Dolores Delgado, Spain’s justice minister, told Parliament that she had been the victim of “political blackmail” by right-wing opponents after a recording was leaked in which Mr. Villarejo asked her during a group lunch to identify any “faggot” among her entourage. Ms. Delgado named Fernando Grande-Marlaska, who is now Spain’s interior minister and is openly gay.

The leader of Podemos, Pablo Iglesias, was among those investigated by Mr. Villarejo.

The leader of Podemos, Pablo Iglesias, was among those investigated by Mr. Villarejo.But the former police commissioner denied being part of a campaign to undermine the party.CreditRafael Marchante/Reuters

In one of his recordings, Mr. Villarejo talks about having seven copies of the conversations that relate to the monarchy’s finances.

In another, a Danish-born aristocrat, Corinna zu Sayn-Wittgenstein, who was romantically linked to King Juan Carlos, can be heard complaining about being used by the monarch to hide some of his wealth offshore.

A spokesman for the royal household declined to comment.

Robin Rathmell — a lawyer for Ms. Zu Sayn-Wittgenstein, who has not been indicted — said, “The abuse she suffered, as a result of desperate attempts by senior Spanish figures to cover up their own financial impropriety, will shortly be laid bare in court.”

In one recording, Mr. Villarejo boasted of earning “a lot of cash” to dig up dirt on behalf of the Spanish state against Catalan politicians, at a time when a secessionist conflict was reaching a boiling point.

That claim is now part of a court investigation into whether Spain’s former conservative government also tried to tarnish opponents in the left-wing Podemos party.

Shortly after Podemos entered Parliament in 2015, shattering Spain’s two-party system, the Spanish news media published articles about how the party and its founder, Pablo Iglesias, were illegally financed by Iranian and Venezuelan money, citing an undisclosed police report.

The conservative party of Mariano Rajoy, the prime minister at the time, used the news to set up a Senate commission to scrutinize the financing of Podemos and other rival parties.

In March, Mr. Villarejo acknowledged in court having investigated Mr. Iglesias as part of a police operation. But he denied being part of a political campaign to discredit Podemos. Mr. Iglesias has denied receiving illegal financing.

Some journalists have been indicted as part of an investigation into whether they helped Mr. Villarejo spread fake media scandals as part of government campaigns to smear opponents.

But Mr. Villarejo is also accused of spying on reporters, like Iñigo de Barron, a financial journalist at the newspaper El País. The journalist has said that his cellphone was tapped by Mr. Villarejo in the summer of 2016, while he was reporting on management changes at BBVA, one of Spain’s largest banks.

BBVA has confirmed that Mr. Villarejo worked for the bank during the long tenure of its former chairman, Francisco González, but it would not say what he was paid for, pending the result of a court investigation in which several other executives of the bank have been indicted.

Mr. González stepped down in December, three months ahead of schedule, just before the Spanish news media released recordings in which Mr. Villarejo and the bank’s security chief can be heard discussing their wiretapping work.

“Villarejo seems to have belonged to a circle of people who believed that they were in privileged positions where they could earn a lot of money while benefiting from complete impunity,” Mr. de Barron said. “What I want to know is how high up this illegal system reached.”

A version of this article appears in print on July 30, 2019, Section A, Page 8 of the New York edition with the headline: The Voice Sending Shudders Through Spain’s Establishment.

No, de debò, el PSOE no és un partit d’esquerres....

L'analista de dades Joe Brew mostra per què el PSOE no és d'esquerres segons

les dades del Pew Research Center

Un dels desafiaments a l’hora d’analitzar la política és la falta de comparabilitat entre diferents països. Les cultures polítiques, els sistemes polítics i els conceptes polítics, fins i tot quan comparteixen un vocabulari semblant, sovint canvien radicalment d’un lloc a un altre. Termes com ara ‘esquerra’ i ‘dreta’, ‘convencional’ i ‘populista’, ‘conservador’ i ‘liberal’, entre més, són emprats regularment, però és qüestionable fins a quin punt un ‘liberal’ espanyol és equivalent, per exemple, a un d’americà. Les paraules signifiquen coses diferents a llocs diferents.

Per totes aquestes diferències, i perquè a l’estat espanyol s’hi han fet moltes enquestes polítiques i molta recerca, les dades a escala internacional tenen un interès especial. Al final del 2017, el Pew Research Center va fer un estudi sobre les actituds polítiques de més de setze mil europeus de vuit països diferents. Ara n’han publicat les dades, cosa que permet d’explorar-ne les variables entre països quant al populisme i la ideologia dreta-esquerra.

Aquest article versa sobre això. Mirem les dades sobre populisme i ideologia dreta-esquerra als països europeus.

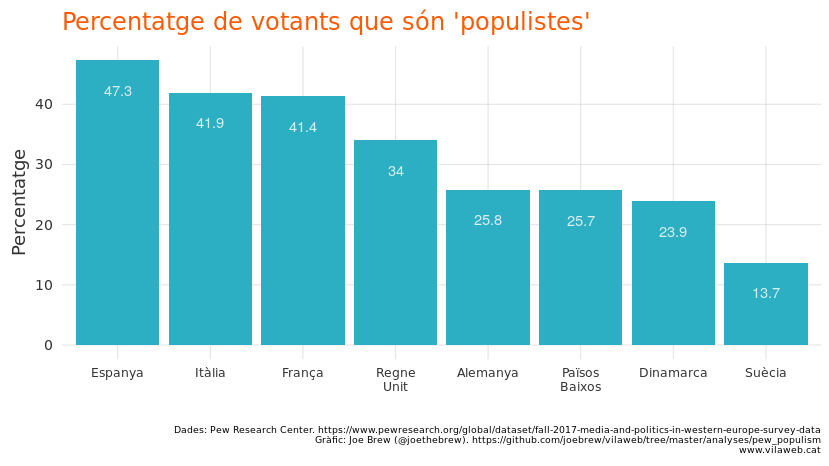

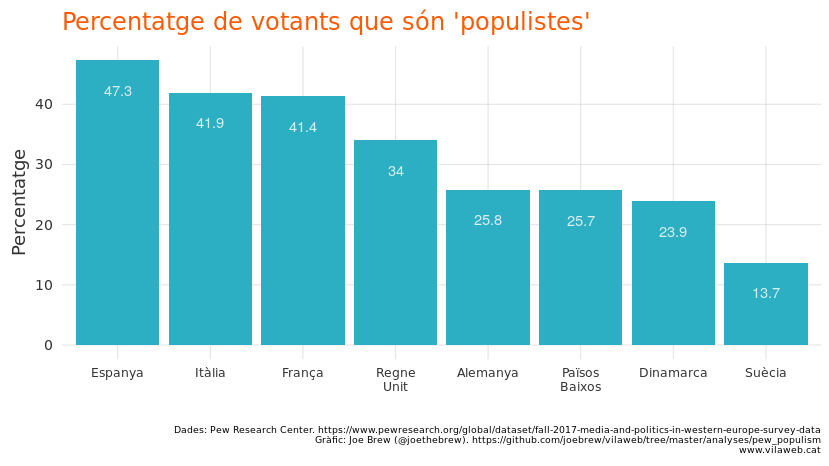

La prevalença del populisme

El Pew Research Center defineix com a ‘populista’ algú que afirma que la gent corrent resoldria més bé els problemes del país que no pas els càrrecs electes i que a la majoria d’aquests últims no els importa què pensa la gent normal com jo. La prevalença del populisme varia molt segons el país. A Alemanya, els Països Baixos i Dinamarca només un de cada quatre votants són populistes, i a Suècia encara menys. Al sud d’Europa, tanmateix, els nivells són molt superiors. Dels vuit països enquestats, Espanya té el nivell més alt: gairebé la meitat dels votants són classificats com a ‘populistes’.

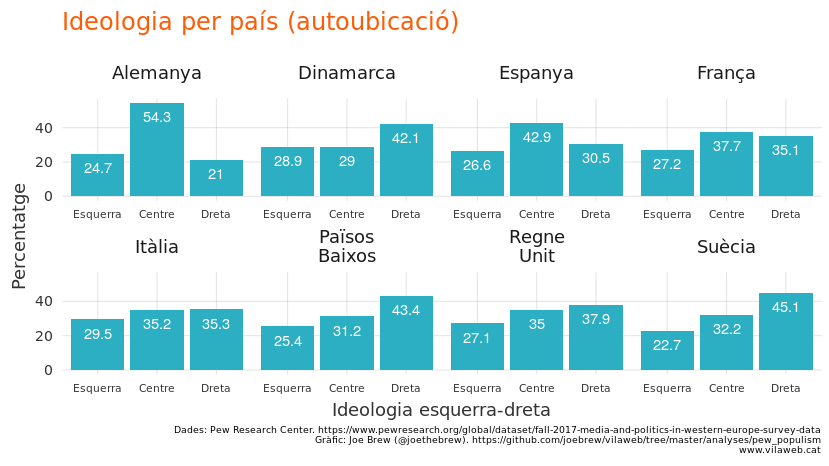

La divisió ideològica dreta-esquerra

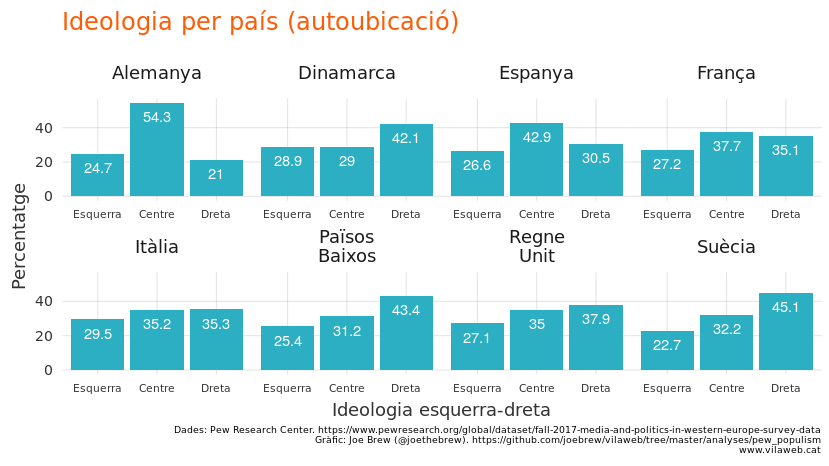

El Pew va demanar als participants de l’enquesta que es classifiquessin en una escala dreta-esquerra del 0 al 6, en què 0-2 era considerat ‘esquerra’, 3 ‘centre’ i 4-6 ‘dreta’. Ací en teniu el desglossament per països:

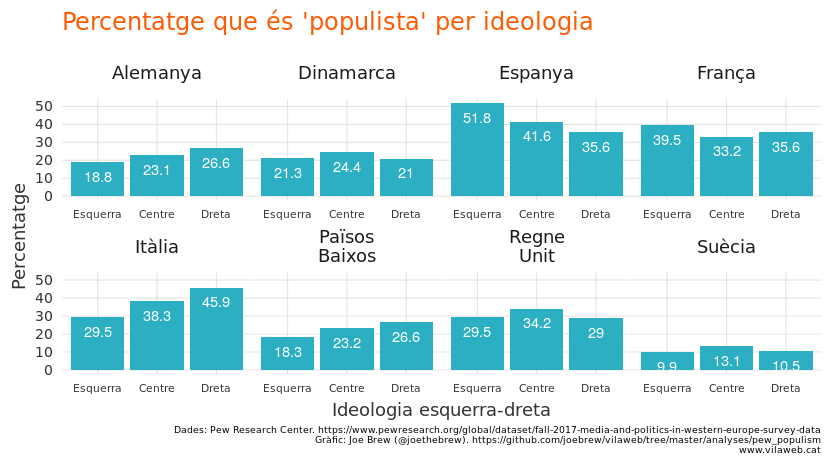

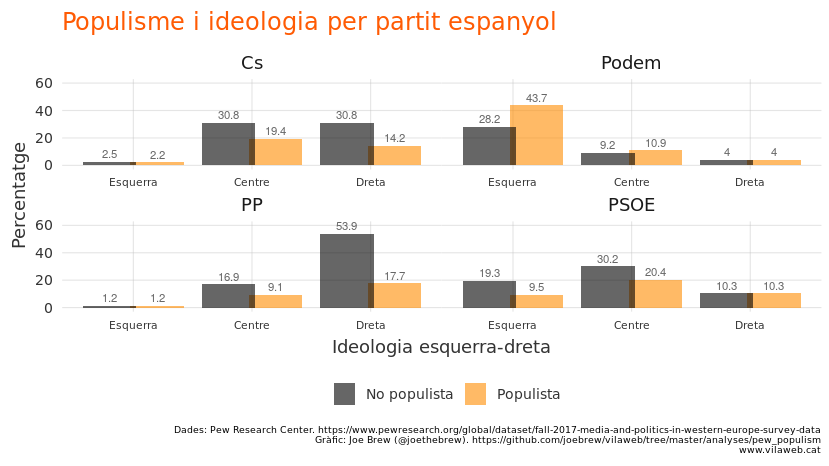

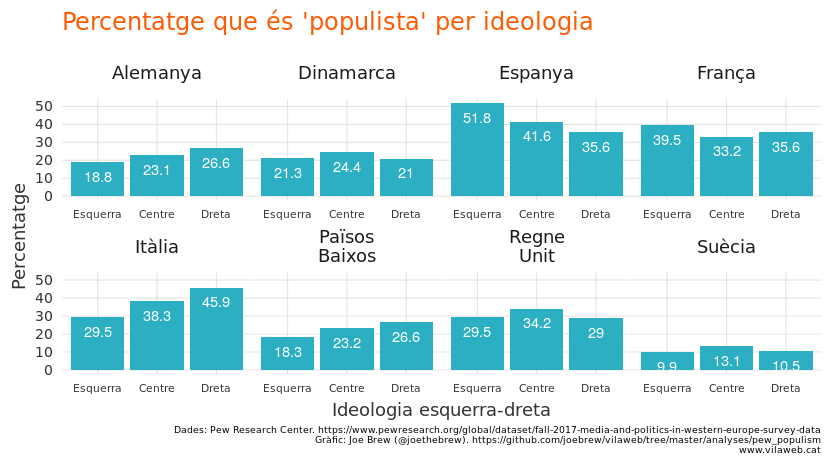

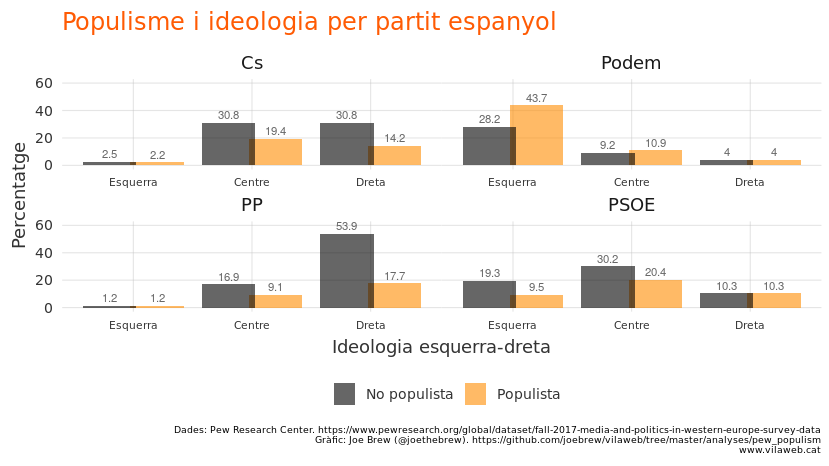

Populisme i eix dreta-esquerra

Ací és on la cosa es posa interessant. A la majoria de països europeus les actituds populistes es concentren en la dreta política o són repartides equitativament entre les ideologies. Però a Espanya el populisme és concentrat fortament en l’esquerra política. Aquest gràfic mostra la prevalença d’actituds populistes (eix y) per ideologia autodefinida (eix x).

Com és que a l’estat espanyol hi ha tant populisme a l’esquerra i n’hi ha relativament poc a la dreta? No ho sé. Però refresquem les dues mesures del Pew per a determinar si algú és populista o no: la creença que la gent corrent resoldria més bé els problemes del país que no pas els càrrecs electes i que a la majoria d’aquests últims no els importa què pensa la normal gent com jo.

Totes dues actituds reflecteixen una desconnexió entre els ciutadans i les institucions que suposadament els representen. Si la causa d’aquesta alienació és simplement una percepció o és realment una representació desproporcionada, no ho sabem.

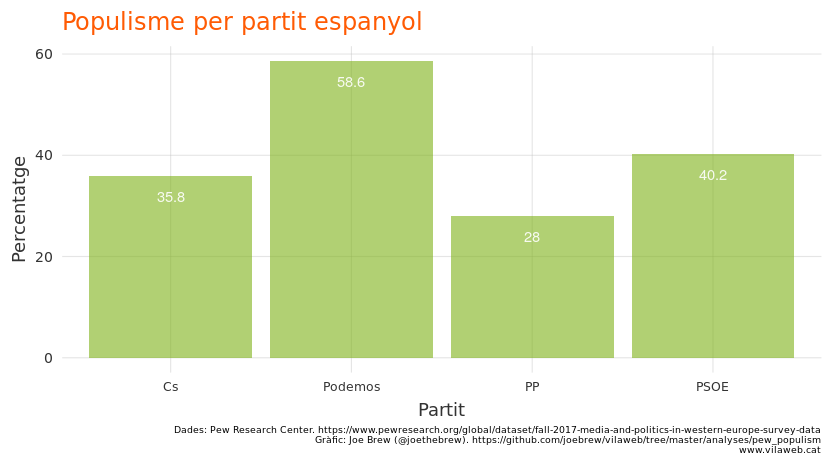

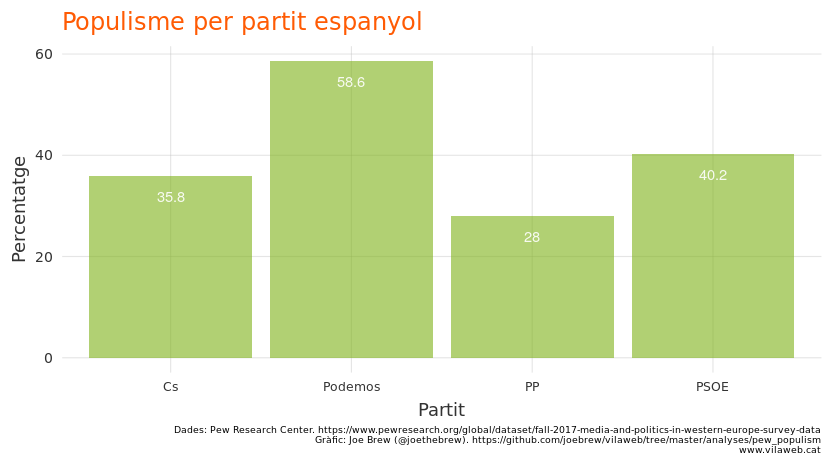

Populisme per partit a Espanya

Segons la definició del Pew, el percentatge de votants populistes a Espanya segons el partit polític és aquesta:

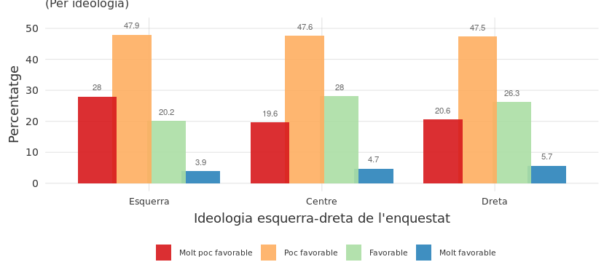

Ideologia i populisme dreta-esquerra

Si mirem el desglossament d’ideologia i populisme per partit, emergeixen algunes coses. La primera, el fet que Podem sigui acusat de partit ‘populista’ s’adequa en gran manera a les dades: més de la meitat dels seus votants encaixen a la definició de ‘populista’ segons el Pew. La segona, la concepció general que el PSOE és un partit de ‘esquerres’ no s’adequa a les dades: A la pregunta del Pew, menys del 30% de votants del PSOE se situen a l’esquerra política. Tercer, el màrqueting de Ciutadans com a partit ‘de centre’ també és contradit per les dades: gairebé la meitat dels seus votants s’ubiquen la dreta política.

Així doncs, el PSOE no és tan d’esquerres?

No, el PSOE no és d’esquerres.

Les dades del Pew mostren que els votants del PSOE són majoritàriament de centre però que una petita minoria d’un de cada cinc és de dretes. Això es correspon amb la manera com veuen el PSOE els espanyols que no el voten. Deixeu-me explicar-ho…

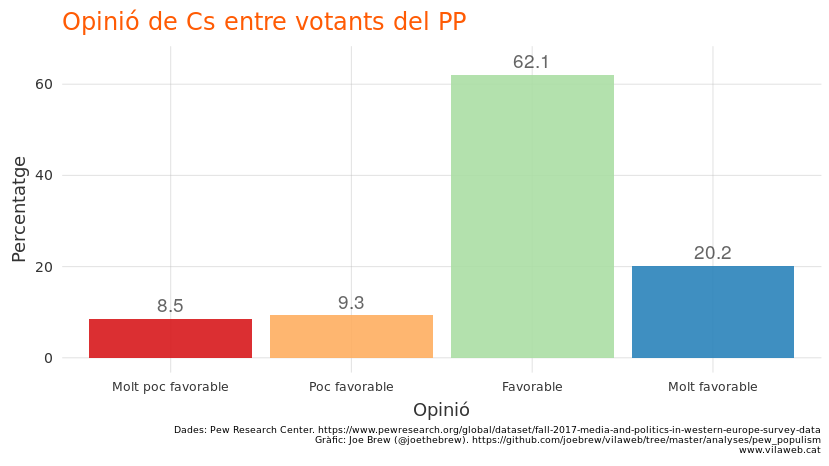

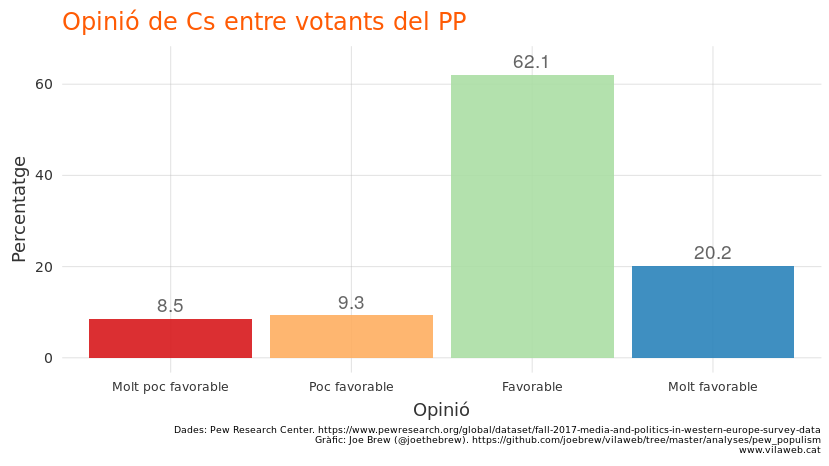

Els votants d’esquerres generalment pensen positivament dels partits de l’esquerra, encara que no sigui el seu. I els votants de dretes, respecte dels altres partits de la dreta, també. Per exemple, els votants del PP, en gran manera, tenen un parer positiu de Ciutadans.

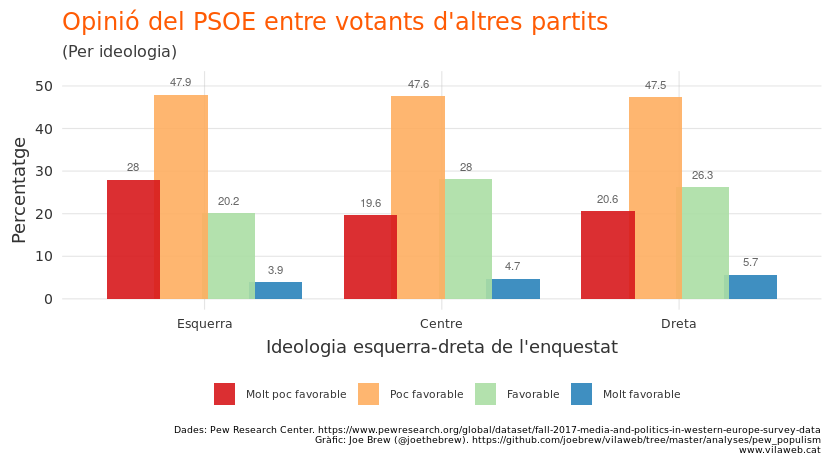

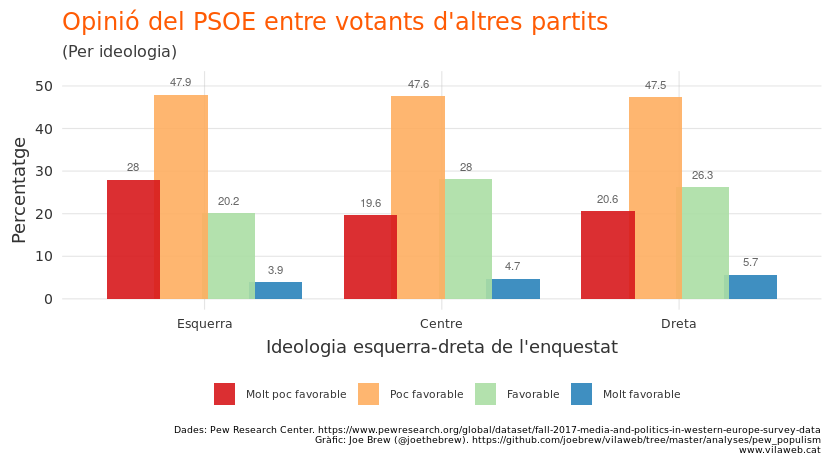

Però què passa quan mirem què pensen del PSOE els ciutadans que no el voten? Si el PSOE fos realment un partit de ‘esquerres’, esperaríem que els votants de l’esquerra en tinguessin opinions més favorables que no pas els de la dreta. En canvi, veiem el cas contrari: la gent de l’esquerra té una opinió més desfavorable del PSOE que no pas la gent de la dreta!

Què passa amb Catalunya?

La mostra del Pew era massa petita per a fer inferències dels partits catalans. Per sort, hi ha bones dades disponibles sobre Catalunya en moltes d’aquestes mateixes qüestions. Els resultats d’aquesta anàlisi (el PSOE no té les característiques d’un partit de ‘esquerres’ malgrat dir-se’n) són congruents amb les dades dels votants a Catalunya en aquesta mateixa qüestió. I quant al populisme, tot i que el nivell d’actituds polítiques segons la classificació del Pew és alta a l’estat espanyol, les característiques populistes són generalment baixes entre els independentistes catalans.

Conclusió

Els termes ‘esquerra’, ‘dreta’ i ‘populista’ es fan servir amb massa facilitat. Els dirigents del PSOE sovint empren el terme ‘esquerra’ o ‘progressista’ per a descriure el seu partit, i ‘populista’ per a descriure els adversaris polítics. Però, si examinem les dades, veiem que aquesta narrativa és desconnectada de la realitat. El 40% dels votants del PSOE són ‘populistes’, un percentatge molt més alt que no pas la mitjana dels vuit països examinats pel Pew. I tant el PSOE com els seus votants no són pas d’esquerres segons els rànquings de favorabilitat per ideologia i segons l’autoubicació en l’escala ideològica.

Nota tècnica

Amb la voluntat de reproductibilitat i transparència, tot el codi i dades emprats per aquest article són disponibles públicament.

les dades del Pew Research Center

Un dels desafiaments a l’hora d’analitzar la política és la falta de comparabilitat entre diferents països. Les cultures polítiques, els sistemes polítics i els conceptes polítics, fins i tot quan comparteixen un vocabulari semblant, sovint canvien radicalment d’un lloc a un altre. Termes com ara ‘esquerra’ i ‘dreta’, ‘convencional’ i ‘populista’, ‘conservador’ i ‘liberal’, entre més, són emprats regularment, però és qüestionable fins a quin punt un ‘liberal’ espanyol és equivalent, per exemple, a un d’americà. Les paraules signifiquen coses diferents a llocs diferents.

Per totes aquestes diferències, i perquè a l’estat espanyol s’hi han fet moltes enquestes polítiques i molta recerca, les dades a escala internacional tenen un interès especial. Al final del 2017, el Pew Research Center va fer un estudi sobre les actituds polítiques de més de setze mil europeus de vuit països diferents. Ara n’han publicat les dades, cosa que permet d’explorar-ne les variables entre països quant al populisme i la ideologia dreta-esquerra.

Aquest article versa sobre això. Mirem les dades sobre populisme i ideologia dreta-esquerra als països europeus.

La prevalença del populisme

El Pew Research Center defineix com a ‘populista’ algú que afirma que la gent corrent resoldria més bé els problemes del país que no pas els càrrecs electes i que a la majoria d’aquests últims no els importa què pensa la gent normal com jo. La prevalença del populisme varia molt segons el país. A Alemanya, els Països Baixos i Dinamarca només un de cada quatre votants són populistes, i a Suècia encara menys. Al sud d’Europa, tanmateix, els nivells són molt superiors. Dels vuit països enquestats, Espanya té el nivell més alt: gairebé la meitat dels votants són classificats com a ‘populistes’.

La divisió ideològica dreta-esquerra

El Pew va demanar als participants de l’enquesta que es classifiquessin en una escala dreta-esquerra del 0 al 6, en què 0-2 era considerat ‘esquerra’, 3 ‘centre’ i 4-6 ‘dreta’. Ací en teniu el desglossament per països:

Populisme i eix dreta-esquerra

Ací és on la cosa es posa interessant. A la majoria de països europeus les actituds populistes es concentren en la dreta política o són repartides equitativament entre les ideologies. Però a Espanya el populisme és concentrat fortament en l’esquerra política. Aquest gràfic mostra la prevalença d’actituds populistes (eix y) per ideologia autodefinida (eix x).

Com és que a l’estat espanyol hi ha tant populisme a l’esquerra i n’hi ha relativament poc a la dreta? No ho sé. Però refresquem les dues mesures del Pew per a determinar si algú és populista o no: la creença que la gent corrent resoldria més bé els problemes del país que no pas els càrrecs electes i que a la majoria d’aquests últims no els importa què pensa la normal gent com jo.

Totes dues actituds reflecteixen una desconnexió entre els ciutadans i les institucions que suposadament els representen. Si la causa d’aquesta alienació és simplement una percepció o és realment una representació desproporcionada, no ho sabem.

Populisme per partit a Espanya

Segons la definició del Pew, el percentatge de votants populistes a Espanya segons el partit polític és aquesta:

Ideologia i populisme dreta-esquerra

Si mirem el desglossament d’ideologia i populisme per partit, emergeixen algunes coses. La primera, el fet que Podem sigui acusat de partit ‘populista’ s’adequa en gran manera a les dades: més de la meitat dels seus votants encaixen a la definició de ‘populista’ segons el Pew. La segona, la concepció general que el PSOE és un partit de ‘esquerres’ no s’adequa a les dades: A la pregunta del Pew, menys del 30% de votants del PSOE se situen a l’esquerra política. Tercer, el màrqueting de Ciutadans com a partit ‘de centre’ també és contradit per les dades: gairebé la meitat dels seus votants s’ubiquen la dreta política.

Així doncs, el PSOE no és tan d’esquerres?

No, el PSOE no és d’esquerres.

Les dades del Pew mostren que els votants del PSOE són majoritàriament de centre però que una petita minoria d’un de cada cinc és de dretes. Això es correspon amb la manera com veuen el PSOE els espanyols que no el voten. Deixeu-me explicar-ho…

Els votants d’esquerres generalment pensen positivament dels partits de l’esquerra, encara que no sigui el seu. I els votants de dretes, respecte dels altres partits de la dreta, també. Per exemple, els votants del PP, en gran manera, tenen un parer positiu de Ciutadans.

Però què passa quan mirem què pensen del PSOE els ciutadans que no el voten? Si el PSOE fos realment un partit de ‘esquerres’, esperaríem que els votants de l’esquerra en tinguessin opinions més favorables que no pas els de la dreta. En canvi, veiem el cas contrari: la gent de l’esquerra té una opinió més desfavorable del PSOE que no pas la gent de la dreta!

Què passa amb Catalunya?

La mostra del Pew era massa petita per a fer inferències dels partits catalans. Per sort, hi ha bones dades disponibles sobre Catalunya en moltes d’aquestes mateixes qüestions. Els resultats d’aquesta anàlisi (el PSOE no té les característiques d’un partit de ‘esquerres’ malgrat dir-se’n) són congruents amb les dades dels votants a Catalunya en aquesta mateixa qüestió. I quant al populisme, tot i que el nivell d’actituds polítiques segons la classificació del Pew és alta a l’estat espanyol, les característiques populistes són generalment baixes entre els independentistes catalans.

Conclusió

Els termes ‘esquerra’, ‘dreta’ i ‘populista’ es fan servir amb massa facilitat. Els dirigents del PSOE sovint empren el terme ‘esquerra’ o ‘progressista’ per a descriure el seu partit, i ‘populista’ per a descriure els adversaris polítics. Però, si examinem les dades, veiem que aquesta narrativa és desconnectada de la realitat. El 40% dels votants del PSOE són ‘populistes’, un percentatge molt més alt que no pas la mitjana dels vuit països examinats pel Pew. I tant el PSOE com els seus votants no són pas d’esquerres segons els rànquings de favorabilitat per ideologia i segons l’autoubicació en l’escala ideològica.

Nota tècnica

Amb la voluntat de reproductibilitat i transparència, tot el codi i dades emprats per aquest article són disponibles públicament.

Sanchez Failed on its own Ego

Twice Sánchez failed to get elected as head of a minority government.(Photo: AFP)

The leftist parties across Europe had trusted him. And now? For reasons of vanity, Sánchez did not manage to forge an alliance. In the end, the rights will probably cheer again.

Comment by Sebastian Schoepp

Since the success of his party in the European elections, the Spaniard Pedro Sánchez claims the role as the last hope of European social democracy. But after this week's spectacle in the Madrid Parliament, one has to say: That's not going to happen. Twice Sánchez failed to get elected as head of a minority government. For the time being, it is a chance to prove that even in 2019 a large European country can still be governed to the left of the center. But how can anyone give an example to Europe's leftists if they can not even come to terms with Podemos' relatively moderate Spanish links?

The fact that Sánchez's ego played a major role in the speech before the decisive vote showed that his principles are more important to him than the position of prime minister. That sums up the whole historic misery of the left: one persists in the conflict with one another so long on principles, until the right wins in the end. This led to absurd situations in the parliamentary debate. Those who are otherwise booked for the role of the rioters, the Basque and Catalan regional parties, pleaded with Sánchez and Podemos boss Pablo Iglesias to tame their egos and not screw up this unique opportunity. Vain. The Catalan left republican Gabriel Rufián put it in a nutshell when he said: That would regret the left yet.

Of course, the regional politicians in Barcelona and Vitoria would be better off with a left-wing government in Madrid than the right-wing concrete faction, the People's Nationalist Party, Ciudadanos and Vox, which, if there were to be new elections in November, would have a chance to win the majority win. But then, in Spain, the inner peace would be in danger, because that would mean the utmost confrontation between Madrid and the regressive regions.

Until September, Sánchez has time to forge a coalition of those willing to talk. The fact that he is so severely involved has historical reasons. At national level, there has never been a coalition government since the reintroduction of democracy in Spain. One of the two major parties has always been strong enough to govern alone or with the occasional help of small parties. The People's Party and Socialists also stuck to this model when Parliament was long since fragmented. As a result, Spain has been run by minority rachit governments for the past few years - holding only until the next budget consultation or no-confidence vote.

The fourth largest economy in the Eurozone, however, needs a concept, a vision, as it comes out of the still smoldering economic crisis. One had the feeling that socialists and podemos certainly had this vision. A more social, but Europe-bound Spain, that could have become a counter-model to the market-liberal uniformity - but especially to the spreading right-wing populism. Sánchez admitted that the two parties were programmatically close together. It is more than negligent to let vanity and vanity fail. It is irresponsible.

Sospechas que se confirman de forma trágica. Quién movía los hilos?

"Dubtem que Es Satty fos un imam o que hagués tingut formació com a imam. No entenem com va arribar a estar al capdavant d'una mesquita."— Miquel Strubell fill 🎗 (@miquelstrubell) July 26, 2019

Ara sí que ho entenem. pic.twitter.com/qmMRI1IqEZ

Ocho 'Ibex 35' pagaron una campaña contra el 'procés' a petición del Gobierno de Rajoy

A PETICIÓN DE LA SECRETARIA DE ESTADO

Los presidentes de las empresas del Ibex 35 se han implicado personal y económicamente en sofocar la independencia de Cataluña promovida por Carles Puigdemont

Parqué del Ibex 35. (EFE)

Parqué del Ibex 35. (EFE)

AGUSTÍN MARCO

TIEMPO DE LECTURA6 min

22/07/2019 05:00 - ACTUALIZADO: 23/07/2019 18:18

Los presidentes de las empresas del Ibex 35 se han implicado personal y económicamente en sofocar el proceso de independencia de Cataluña promovido por la Generalitat de Cataluña. Según han confirmado varias fuentes oficiales, siete de las mayores compañías nacionales financiaron a petición de Mariano Rajoy una campaña internacional por las principales capitales de Europa y ciudades de Estados Unidos para contrarrestar la propaganda del Gobierno catalán en el extranjero.

En octubre de 2017, España vive un momento político histórico ante el envite del entonces presidente de la Generalitat, Carles Puigdemont, al declarar la independencia de Cataluña y forzar la celebración del referéndum del 1 de octubre. La Generalitat utiliza sus embajadas en el exterior para plantear el debate sobre su proyecto secesionista como una lucha entre el espíritu democrático del referéndum y el totalitarismo de Madrid por impedirlo. Y el discurso cala en algunos medios de comunicación internacionales. La declaración de independencia del Parlamento de Cataluña del 27 de octubre recibe inmediatamente la respuesta del Gobierno de Mariano Rajoy, que aprueba la aplicación del artículo 155 de la Constitución para intervenir el parlamento regional.

A la par, Carmen Martínez de Castro, secretaria de Estado de Comunicación dentro del Ministerio de Presidencia, convoca a un desayuno a altos directivos de Banco Santander, BBVA, Caixabank, Telefónica, Repsol, Iberdrola, El Corte Inglés e Inditex. Les explica el momento tan delicado que vive España y las posibles consecuencias para el país y para las empresas del órdago independentista. En ese contexto, del que todos los presentes eran conscientes, la mano derecha del que era presidente español en ese momento, Mariano Rajoy, les pide que contribuyan a neutralizar la campaña mediática de la Generalitat, en una operación que se estructuraría a través del Real Instituto Elcano, cuyo presidente de honor es el rey Felipe VI.

![]() Pinche para ampliar el documento.

Pinche para ampliar el documento.

Tras debatir cuál es la mejor fórmula para instrumentar esta ayuda -en un momento en el que muchas empresas estaban cambiando sus sedes en Cataluña y otras estaban viendo sus negocios en riesgo-, se consideró adecuado que la campaña se ejecutara a través del Real Instituto Elcano, dado que todas ellas forman parte de su patronato. De esa manera, se quiso evitar dar la impresión de que estas empresas estuviesen financiando una acción gubernamental.

Según la documentación a la que ha tenido acceso El Confidencial, la idea era montar un 'road show' o ciclo de conferencias por cinco ciudades europeas --París, Londres, Bruselas, Berlin y Roma-- y dos estadounidenses, Nueva York y Washington. El Real Instituto Elcano quería contar con la colaboración de 'think tanks' como el Institut Français Relations Internationales, Chatham House, Egmont, Institut für Euroapaische Politik, Istituto Affari Internazionali, Wilson Center Peterson Institute for International Economics y el council on Foreign Relations. Finalmente solo participaron dos, Chatham House y el Wilson Center. La ronda comenzó el 6 de noviembre en Londres y acabó el 19 de diciembre en Nueva York.

Además del director del Real Instituto Elcano, Charles Powell y varios de sus principales investigadores, la documentación preparatoria que se presentó a los potenciales financiadores contemplaba la participación de Josep Bou, presidente de Empresaris de Catalunya; Joaquím Gay de Montella, en ese momento presidente de Foment del Treball; de Juan Rosell, presidente de la CEOE; Josep Borrell, actual ministro de Exteriores en funciones y entonces barajado como miembro de la sociedad civil; o Josep Piqué, exministro y consejero de varias compañías como Amadeus, Alantra y antes OHL y Aena.

Sin embargo, de los mencionados en el papel, solo acabaron participando los analistas del Real Instituto Elcano; Ignasi Guardans, socio de K&L Gates y exeurodiputado por Convergència, y Sandra León, profesora de la Universidad de York. El resto de vacantes fueron ocupadas por otros analistas independientes. Fuentes de la institución aseguran que ninguno de ellos cobró y que solo se financiaron los desplazamientos. Según ha afirmado el Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores en un comunicado, Borrell desconocía esta campaña, no intervino en las jornadas, ni tampoco recibió ninguna llamada invitándole al evento. Fuentes cercanas al presidente del Grupo Colonial y del Cercle d'Economia, Juan José Brugera, se han puesto en contacto con este medio para aclarar que, a pesar de salir en el programa tentativo, no fue informado, ni invitado, ni participó en ningún acto vinculado a esta iniciativa.

![]()

AMPLIARDocumento preparatorio con el programa tentativo que se ofreció a las empresas que acabaron financiando la campaña

Fuentes de las empresas financiadoras, que oficialmente han declinado hacer ningún comentario, explican que la situación particular de España exigía una respuesta contundente y que el Real Instituto Elcano era y es una organización respetada a nivel internacional para exponer al mundo que en el país se respetaba el orden constitucional. Una estructura que en aquellos días estaba en peligro por la amenaza independentista que había conseguido tener altavoces en medios extranjeros de primer orden.

Por ello, estas empresas acordaron dar un "presupuesto especial" para esta campaña, a petición del Gobierno, puesto que Elcano ya había consumido prácticamente los cinco millones con los que un gran número de compañías nacionales financian anualmente al Instituto. La aprobación de esta línea tuvo que ser validada por cada uno de los presidentes de Banco Santander, BBVA, Caixabank, Telefónica, Repsol, Iberdrola, El Corte Inglés e Inditex con el fin de acreditar la importancia de la orden recibida desde Moncloa.

Fuentes oficiales de Elcano indican que entre los mandatos fundacionales de la institución está explicar España al mundo y el mundo a los españoles. Sobre el 'road show' pagado por estas empresas, indican que "el 24 de octubre de 2017, el Real Instituto Elcano presentó en rueda de prensa el informe "El proceso independentista catalán ¿cómo hemos llegado hasta aquí?", con una gran presencia de medios, entre ellos muchos corresponsales extranjeros". Por ello, visto el interés suscitado y que muchos de esos periodistas habían asumido como verdaderas las tesis independentistas, se decidió hacer esta misma presentación en otros países, "a través de los centros de pensamiento con los que tenemos una relación habitual".

El objetivo era "explicar la situación en Cataluña, y defender los intereses y la imagen de España". Para ello, la idea se comunicó a los miembros del Patronato y se solicitó un presupuesto adicional, ya que no estaba incluido en el presupuesto de 2017. Por contra, Elcano asegura desconocer la participación del Gobierno y por qué la Secretaria de Estado de Comunicación fue la que pidió la aportación de las compañías al Instituto en una reunión en Moncloa cuando lo podía haber hecho directamente el patronato donde están sentados representantes de Banco Santander, BBVA, Caixabank, Telefónica, Repsol, Iberdrola, El Corte Inglés e Inditex.

Los presidentes de las empresas del Ibex 35 se han implicado personal y económicamente en sofocar la independencia de Cataluña promovida por Carles Puigdemont

Parqué del Ibex 35. (EFE)

Parqué del Ibex 35. (EFE)AGUSTÍN MARCO

TIEMPO DE LECTURA6 min

22/07/2019 05:00 - ACTUALIZADO: 23/07/2019 18:18

Los presidentes de las empresas del Ibex 35 se han implicado personal y económicamente en sofocar el proceso de independencia de Cataluña promovido por la Generalitat de Cataluña. Según han confirmado varias fuentes oficiales, siete de las mayores compañías nacionales financiaron a petición de Mariano Rajoy una campaña internacional por las principales capitales de Europa y ciudades de Estados Unidos para contrarrestar la propaganda del Gobierno catalán en el extranjero.

En octubre de 2017, España vive un momento político histórico ante el envite del entonces presidente de la Generalitat, Carles Puigdemont, al declarar la independencia de Cataluña y forzar la celebración del referéndum del 1 de octubre. La Generalitat utiliza sus embajadas en el exterior para plantear el debate sobre su proyecto secesionista como una lucha entre el espíritu democrático del referéndum y el totalitarismo de Madrid por impedirlo. Y el discurso cala en algunos medios de comunicación internacionales. La declaración de independencia del Parlamento de Cataluña del 27 de octubre recibe inmediatamente la respuesta del Gobierno de Mariano Rajoy, que aprueba la aplicación del artículo 155 de la Constitución para intervenir el parlamento regional.

A la par, Carmen Martínez de Castro, secretaria de Estado de Comunicación dentro del Ministerio de Presidencia, convoca a un desayuno a altos directivos de Banco Santander, BBVA, Caixabank, Telefónica, Repsol, Iberdrola, El Corte Inglés e Inditex. Les explica el momento tan delicado que vive España y las posibles consecuencias para el país y para las empresas del órdago independentista. En ese contexto, del que todos los presentes eran conscientes, la mano derecha del que era presidente español en ese momento, Mariano Rajoy, les pide que contribuyan a neutralizar la campaña mediática de la Generalitat, en una operación que se estructuraría a través del Real Instituto Elcano, cuyo presidente de honor es el rey Felipe VI.

Tras debatir cuál es la mejor fórmula para instrumentar esta ayuda -en un momento en el que muchas empresas estaban cambiando sus sedes en Cataluña y otras estaban viendo sus negocios en riesgo-, se consideró adecuado que la campaña se ejecutara a través del Real Instituto Elcano, dado que todas ellas forman parte de su patronato. De esa manera, se quiso evitar dar la impresión de que estas empresas estuviesen financiando una acción gubernamental.

Según la documentación a la que ha tenido acceso El Confidencial, la idea era montar un 'road show' o ciclo de conferencias por cinco ciudades europeas --París, Londres, Bruselas, Berlin y Roma-- y dos estadounidenses, Nueva York y Washington. El Real Instituto Elcano quería contar con la colaboración de 'think tanks' como el Institut Français Relations Internationales, Chatham House, Egmont, Institut für Euroapaische Politik, Istituto Affari Internazionali, Wilson Center Peterson Institute for International Economics y el council on Foreign Relations. Finalmente solo participaron dos, Chatham House y el Wilson Center. La ronda comenzó el 6 de noviembre en Londres y acabó el 19 de diciembre en Nueva York.

Además del director del Real Instituto Elcano, Charles Powell y varios de sus principales investigadores, la documentación preparatoria que se presentó a los potenciales financiadores contemplaba la participación de Josep Bou, presidente de Empresaris de Catalunya; Joaquím Gay de Montella, en ese momento presidente de Foment del Treball; de Juan Rosell, presidente de la CEOE; Josep Borrell, actual ministro de Exteriores en funciones y entonces barajado como miembro de la sociedad civil; o Josep Piqué, exministro y consejero de varias compañías como Amadeus, Alantra y antes OHL y Aena.

Sin embargo, de los mencionados en el papel, solo acabaron participando los analistas del Real Instituto Elcano; Ignasi Guardans, socio de K&L Gates y exeurodiputado por Convergència, y Sandra León, profesora de la Universidad de York. El resto de vacantes fueron ocupadas por otros analistas independientes. Fuentes de la institución aseguran que ninguno de ellos cobró y que solo se financiaron los desplazamientos. Según ha afirmado el Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores en un comunicado, Borrell desconocía esta campaña, no intervino en las jornadas, ni tampoco recibió ninguna llamada invitándole al evento. Fuentes cercanas al presidente del Grupo Colonial y del Cercle d'Economia, Juan José Brugera, se han puesto en contacto con este medio para aclarar que, a pesar de salir en el programa tentativo, no fue informado, ni invitado, ni participó en ningún acto vinculado a esta iniciativa.

AMPLIARDocumento preparatorio con el programa tentativo que se ofreció a las empresas que acabaron financiando la campaña

Fuentes de las empresas financiadoras, que oficialmente han declinado hacer ningún comentario, explican que la situación particular de España exigía una respuesta contundente y que el Real Instituto Elcano era y es una organización respetada a nivel internacional para exponer al mundo que en el país se respetaba el orden constitucional. Una estructura que en aquellos días estaba en peligro por la amenaza independentista que había conseguido tener altavoces en medios extranjeros de primer orden.

Por ello, estas empresas acordaron dar un "presupuesto especial" para esta campaña, a petición del Gobierno, puesto que Elcano ya había consumido prácticamente los cinco millones con los que un gran número de compañías nacionales financian anualmente al Instituto. La aprobación de esta línea tuvo que ser validada por cada uno de los presidentes de Banco Santander, BBVA, Caixabank, Telefónica, Repsol, Iberdrola, El Corte Inglés e Inditex con el fin de acreditar la importancia de la orden recibida desde Moncloa.

Fuentes oficiales de Elcano indican que entre los mandatos fundacionales de la institución está explicar España al mundo y el mundo a los españoles. Sobre el 'road show' pagado por estas empresas, indican que "el 24 de octubre de 2017, el Real Instituto Elcano presentó en rueda de prensa el informe "El proceso independentista catalán ¿cómo hemos llegado hasta aquí?", con una gran presencia de medios, entre ellos muchos corresponsales extranjeros". Por ello, visto el interés suscitado y que muchos de esos periodistas habían asumido como verdaderas las tesis independentistas, se decidió hacer esta misma presentación en otros países, "a través de los centros de pensamiento con los que tenemos una relación habitual".

El objetivo era "explicar la situación en Cataluña, y defender los intereses y la imagen de España". Para ello, la idea se comunicó a los miembros del Patronato y se solicitó un presupuesto adicional, ya que no estaba incluido en el presupuesto de 2017. Por contra, Elcano asegura desconocer la participación del Gobierno y por qué la Secretaria de Estado de Comunicación fue la que pidió la aportación de las compañías al Instituto en una reunión en Moncloa cuando lo podía haber hecho directamente el patronato donde están sentados representantes de Banco Santander, BBVA, Caixabank, Telefónica, Repsol, Iberdrola, El Corte Inglés e Inditex.

Monday, 22 July 2019

Brutal situación actual política surreal clásica país colonial!

▶@gabrielrufian a Sánchez: "Tengo 1 noticia para usted: no tiene mayoría absoluta.🤔¿Qué hace ignorando durante 2 horas de discurso de investidura Catalunya? Ninguna mención, 0. Y resulta que es el principal conflicto político"— Esquerra Republicana (@Esquerra_ERC) July 23, 2019

❕Els millors moments a la #SesiónDeInvestidura👇 pic.twitter.com/vvY682rkkt

Judge Marchena Laughing at Jurisprudence and Law with reporters when asked about the sentences in the #CatalanTrial

"Is this really permissible, Judge #Marchena laughing it up with reporters when asked about the sentences in the #CatalanTrial posing in front of the #Santander logo? #staging" https://t.co/q9lTtLsdfS pic.twitter.com/6C9Y37ZiHT— barbaryfigs (@milfordedge) July 24, 2019

Wednesday, 17 July 2019

El Estado español estaba al tanto que se iba a cometer atentados en Cataluña y no lo evitó

1

2La televisión pública vasca se hace eco del mayor escándalo de los últimos tiempos, que los medios españoles intentan silenciar: El Estado español estaba al tanto que se iba a cometer atentados en Cataluña y no lo evitó. [Parte 1]— Superwoman Roja (@superwomanroja) July 17, 2019

¡DIFUNDE! pic.twitter.com/irVGR9D4gl

A tan solo 2 meses del referéndum del 1 de octubre, quien piense que fue casualidad no conoce hasta dónde está dispuesto a llegar el Estado fascista español en Cataluña. [Parte 2] pic.twitter.com/zL90g0ak53— Superwoman Roja (@superwomanroja) July 17, 2019

Tuesday, 16 July 2019

El cerebro del atentado en Las Ramblas era confidente del CNI hasta el día de los atentados

Así lo confirma la primera exclusiva que ha publicado hoy Publico, y que anuncia que habrá más información al respecto de estos atentados, que están llenos de incógnitas

Por Beatriz Talegón

-16/07/2019

1

Según el resultado de la investigación que se ha venido realizado por su parte, Público «puede asegurar que ese imán de Ripoll seguía siendo considerado informador de los servicios secretos españoles -por ellos mismos- el día en que su discípulo Younes Abouyaaquob asesinó a 13 personas, hace dos años».

Una contundente afirmación que abre una serie de interrogantes y que, previsiblemente, vendrá acompañada de más información exclusiva en próximas fechas, puesto que el artículo que hoy se publica viene numerado como (1).

En la pieza publicada hoy Bayo explica el método de comunicación que habían establecido entre el Centro Nacional de Inteligencia (CNI) y su confidente «más secreto», el imán de Ripoll, Abdelbaki es Satty, cabecilla de los terroristas que cometieron la matanza de las Ramblas de Barcelona hace dos años. Se explica de manera detallada el sistema de transmisión de información denominado «correo muerto», una forma de comunicación que según los expertos es imposible de interceptar porque «jamás se transmiten datos por internet». Este sistema, según se explica en la interesante e imprescindible pieza es usada en el mundo del espionaje y se hacen eco también de ella varios manuales terroristas de Al Qaeda que son accesibles a través de Internet.

Según informa Público, el CNI conocía los planes de los terroristas en sus viajes. Y es que el grupo terrorista viajó a Suiza, a Alemania, a Francia, a Bélgica conduciendo el mismo Audi A3 que utilizarían después en el atentado en Cambrils. Los agentes del CNI estaban siguiendo minuciosamente todos sus movimientos «conociendo previamente sus planes». Escuchaban sus llamadas y sabían los motivos de sus viajes, lo que pretendían comprar y lo que, supuestamente, pretendían hacer con ello. Se preguntan en el artículo «¿cómo es posible que los servicios secretos españoles estén al corriente de todos esos detalles, incluidas las conversaciones entre los terroristas sobre sus proyectos y objetivos, pero no ponga fin a esas actividades de preparación de los atentados?». Es más, Público asegura que «el servicio secreto español seguía vigilando y controlando a los terroristas hasta el mismo día del atentado de Las Ramblas, puesto que no fue hasta la mañana siguiente de la masacre cuando se borró del registro central de fuentes del CNI la ficha del mismísimo Es Satty».

En una entrevista publicada por 20minutos el 19 de diciembre de 2017 el Presidente Puigdemont habló claro, y curiosamente, sus declaraciones no tuvieron el recorrido que, ante la relevancia de lo que manifestó, podría haberse esperado.

En esta entrevista Carles Puigdemont apunta lo siguiente: ante la pregunta de si es cierto que el Gobierno les amenazó con sangre en la calle, el Presidente responde: Las conexiones del imán de Ripoll con el CNI se han demostrado. Sin embargo, si yo lo hubiera dicho en agosto, que teníamos esta percepción, seguramente no habría podido decir nada más que eso. Yo creo que con el tiempo -también hay que poner distancia, porque es un tema muy serio- vamos a conocer más cosas. Hemos sabido más recientemente que había unos planes de asalto a la Generalitat, al Parlament, no creo que fueran para repartir flores… vimos lo que pasó el 1 de octubre. Vimos, hemos leído y escuchado portavoces del gobierno español decir explícitamente que van a hacer todo para impedir la independencia de Cataluña. Yo, sin embargo, he dicho y repito que para la independencia yo no estoy dispuesto a todo: hay algo que nunca voy a estar dispuesto que es la violencia y a la vía no democrática. Y este compromiso yo no lo he escuchado del Gobierno español.

Por tanto, ante esto, evidentemente uno tiene que tomar su responsabilidad. Yo soy el responsable de todos los catalanes, no sólo de una parte, de todos. Y ante el riesgo, acreditado, de que pudiera haber una confrontación violenta, yo decidí lo que decidí y de esto no me arrepiento. Si hay alguien al otro lado tan irresponsable que quiere jugar con este lenguaje, yo no lo voy a hacer».

Aquí puede ver el extracto concreto al que nos referimos:

España ESCUCHA. La violencia jamás ha venido de los independentistas.

3.211

12:43 - 16 jul. 2019

Información y privacidad de Twitter Ads

1.937 personas están hablando de esto

«A mediados de agosto pasarán cosas en Cataluña»: el mensaje que García-Margallo dio el 10 de julio de 2017

Precisamente, desde que se ha publicado por Público la exclusiva, que a su vez confirma lo que también había publicado hace un año el diario Las Repúblicas, está moviéndose este artículo de elMon, donde se recogen las declaraciones que el es-ministro García-Margallo hizo días antes de los atentados.

Aseguraba en el mes de julio que «el Estado no puede tolerar ningún acto de desobediencia en Cataluña», instando a «volver a la razón al considerar que, se resuelvan o no los incidentes puntuales, sería bueno analizar el problema de la desafección de parte de la sociedad catalana con las otras Españas». Según informaba este artículo, «A su juicio, a partir de la segunda quincena de agosto comezarán a «pasar cosas» en Cataluña y el presidente de la Generalitat, Carles Puigdemont, tendrá dificultades con su partido, con ERC, la CUP y también con sectores sociales importantes, como los empresarios y comerciantes, la tradicional burguesía catalana.» Continuaba la pieza señalando las palabras del ex ministro: «esta es una tragicomedia en la que nadie sabe cuál es el final y nadie sabe qué pasará al día siguiente, ya que en el campo soberanista o secesionsita cada uno parece tener su propia agencia, lo que no sólo no facilita una solución del proceso, sino que lo dificulta». Terminaba la pieza con una frase en negrita: «prevé un agosto y septiembre «muy complicado».

Discurso del 26 de octubre del President: «No hay intención de parar la represión ni de procurar unas condiciones de ausencia de violencia en que unas posibles elecciones se hubieran podido celebrar».

El 20 de octubre de 2017 Puigdemont da un discurso en el cual no acepta la decisión de aplicar el artículo 155 de la Constitución, como tampoco convoca elecciones, atendiendo a las circunstancias que se estaban produciendo.

Pone en manos de la mayoría parlamentaria que decida al respecto de las medidas sobre el artículo 155 de la CE. Un discurso lleno de contenido, que en algunos puntos, pudo pasar desapercibido pero que hoy tiene más sentido que nunca. Precisamente apunta al hecho de que no se puede garantizar la ausencia de violencia desde el gobierno español.

«El compromiso con la paz y el civismo se mantienen más firmes que nunca». Así terminó su intervención. Un claro mensaje que posicionaba al independentismo catalán frente una violencia que se había señalado, pero que no se entendió en ese momento.

Marta Rovira asegura que el Gobierno amenazó con «muertos en la calle» tras el 1 de octubre

Así titulaba el 17 de noviembre este artículo el diario Público. Apuntan a que «la Secretaria General de ERC, Marta Rovira, había asegurado que el gobierno amenazó al exgovern de la Generalitat con «violencia extrema con muertos en la calle» si, tras el referendum del 1 de octubre, no ponían fin al proceso independentista.»

Y reproduce las declaraciones que la líder de ERC había hecho en RAC1: «Directamente nos decían esto: que habría sangre y que teníamos que parar porque no dudarían esta vez, y que esta vez no serían pelotas de goma». No desveló en aquel momento quién había avisado al President, pero sí se mostró a hacerlo en el momento oportuno. Y afirmaba que tanto Puigdemont como Junqueras confirmaban que las fuentes eran contrastadas.

«Nos falta información del CNI para completar el puzzle del 17-A»