Twenty years after the end of the Spanish Civil War, photographer Michael Peto travelled around Spain with writer Nora Beloff for a three part series in the Observer looking at different aspects of life under General Franco and the future for the country.

All photographs by Michael Peto for the Observer/Courtesy of the University of Dundee, The Peto Collection.

One of Spain’s principal attractions to it’s millions of visitors from industrial Northern Europe - besides sunshine and cheap services - is the archaism of the countryside.

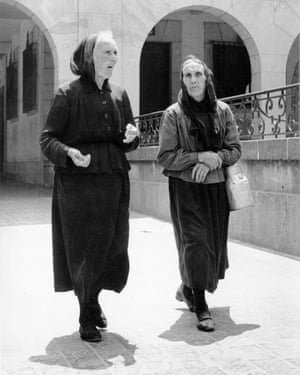

You can drive for hundreds of miles and, apart from a patchy and uncertain tarmac under your tyres, there is nothing to remind you of the twentieth century: no poles or pylons, no petrol stations or electric pumps, just the peasants and their children in floppy hats and dateless clothes, women carrying pitchers on their heads and the two commonest landmarks, the donkey and the Cross.

All this produces an illusion of permanence: so these people have always lived and so it seems they always will.

The illusion is false: and the tourists themselves are one of the reasons why. their disturbing impact on old Spain was noted by the National Association of Fathers of Families, one of the major corporations now authorised in Spain, who said at it’s annual congress this year: ‘It is impossible to overlook the danger represented in certain regions of Spain by the tourist current as a vehicle of ideas and customs highly pernicious to our family morality...’

Primarily Spanish farming is being forced away from its primitivism by the reproduction rate of the Spaniards themselves. The population has increased by five million since the Civil War, and a European country with the lowest agricultural yield and the highest birth-rate is condemned to modernise or die. The switching of public investment from industry to agriculture, notable in irrigation, has, in fact, already been decided upon.

The change is being accelerated by the penetration into rural Spain of Western notions of progress. This comes partly from the tourists, but also from a plentiful provision of American films (very cheap and available in local currency under the American Aid Agreement) in village cinemas and from the spread of radio. But the decisive fact has been the migration of surplus labour into the cities, so that hardly any peasant family is without a cousin, brother or child to bring it into touch with the modern world.

An old lady from a remote mountain village in the Asturias said she had had seventeen children, but added with a chuckle that her eldest daughter had married in the nearby town and had had only three;’They are cleverer these days...’

Crowding into cities is a common enough feature in the modern world but in Spain it has reached catastrophic proportions. Madrid (now two million) and Barcelona (one and a half million) are in a state of siege. Every day police patrol the platforms when the trains from the west and south arrive and peasants without labour permits are sent back on the next train at public expense. They find other ways of slipping back.

There are today 120.000 of these immigrants grouped in the outlying slums of Barcelona. Some we visited have built their homes on the beaches by the railway track, regardless of the stench, where the sewers tip their contents into the sea. You can see them with buckets trying to fish food out of the filth. Bureaucrats have visited the site, declared it insalubrious, and forbidden further building. So now when, as frequently happens, the waves knock down existing shacks, families have to move in together.

Leaving aside the sub-proletariat of the slums, who sell their services far below the minimum wage, labourers have suffered far less from inflation than white-collar workers and school teachers whose standard of life has sunk far below conditions before the Civil War. Many Spaniards will tell you that the Government is deliberately pursuing what an orange-dealer from Valencia called the ‘cretinisation’ of the Spanish people: demoting and starving the intellectuals (who are traditionally anti-militarist, anti-clerical and anti-Franco) and boosting the current football craze (which has now ousted bull-fighting in popular favour) by radio, television, liberal allocation of newsprint to sports papers, and the building of colossal stadia.

The quest for the colossal is indeed a typical feature of Spain’s social policy. The skyline of many provincial cities is dominated no longer by the steeple but by some great State edifice, often the Social Security clinic.

This is an edited extract from an article by Nora Beloff entitled ‘What’s Happening in Spain?’, published in the Observer on 19 July 1959.

No comments:

Post a Comment