¿Y si España hubiera quedado dividida tras la Guerra Civil?

18JUL 2016

Compartir:

Iñaki Berazaluce

En marzo de 1937, la Guerra Civil española había llegado a una situación de tablas: la mitad oriental de la península permanecía fiel al Gobierno republicano, mientras Galicia, Castilla y la Andalucía occidental, de Málaga a Huelva, había caído bajo el control de los militares golpistas. En la cornisa cantábrica, una franja poblada por irreductibles republicanos resistía al invasor desde Bilbao a Santander.

El brutal bombardeo de Guernica por parte de la Legión Cóndor y la aviación italiana al servicio de las tropas sublevadas determina la entrada en la guerra de la URSS que, hasta entonces, había prestado un tímido apoyo militar al Gobierno republicano de Manuel Azaña. La intervención soviética no fue gratuita: Stalin exigió a Azaña la revocación de Largo Caballero como jefe de Gobierno y su reemplazo por la prominente comunista Dolores Ibárruri, La Pasionaria.

Los 20.000 hombres de la 3ª División del Ejército Rojo al mando del general Georgy Zhuzov desembarcaron en mayo del 37 en el puerto de Valencia desde su base en Odessa. Zhukov llegó a España en calidad de asesor militar del Gobierno republicano, pero tras la exitosa campaña de Aragón, que cambió el curso de la guerra y abrió un corredor que conectó Barcelona, Zaragoza y Bilbao, fue ascendido a Ministro de la Guerra por Ibárruri, obediente a las órdenes de Moscú.

La contraofensiva republicana provocó las primeras divisiones internas entre la cúpula militar golpista. El general Queipo de Llano confabuló contra sus rivales del «ejército moro» y el general Franco fue señalado como culpable de la derrota de la Batalla de Zaragoza. Franco fue degradado a teniente y recluido en Melilla acusado de «alta traición» a la Junta de Defensa Nacional. Dos años más tarde, en 1939, fue fusilado tras liderar un cuartelazo secundado por varios mandos de la Legión africana.

Bandera de la España soviética, Alt Historia.

El frente de batalla de 1938, que dividía casi parejamente la península de sur a norte, fue enquistándose hasta convertirse en una frontera. El avance del Ejército Rojo fue frenado por el estallido de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, en tanto que la URSS detuvo el envío de tropas y material bélico hacia España, preparándose como estaba para la inevitable confrontación con la Alemania nazi.

El 1 de octubre de 1940, el Triunvirato Militar que integraban Queipo de Llano, Mola y Sanjurjo nombra presidente de la «España Libre» a José María Gil-Robles, que había ejercido de ministro de la Guerra con Lerroux durante la II República. El Gobierno de Gil-Robles, siempre bajo la estrecha vigilancia de sus valedores espadones, se instala en Sevilla, «reserva espiritual» de la «España liberada».

Entre tanto, La Pasionaria inicia desde Madrid la sovietización del campo en laRepública Democrática de España. Las tierras de labranza de Cataluña, Valencia, Aragón, Murcia y la mitad oriental de Andalucía y Castilla son requisadas a sus dueños y cedidas a consejos de obreros y campesinos, un «doloroso pero necesario» proceso orquestado por el comisario Juan Negrín, instruido previamente en el Sóviet de Petrogrado.

El control de los Pirineos por parte de los rusos fue clave en la derrota del Eje en la conflagración mundial. La «España Libre» quedó a merced del Ejército Rojo, pero el desembarco de Lisboa (1944) por parte del Ejército de EE UU logró frenar las tentativas expansionistas de Stalin en la península Ibérica. El general Patton puso el I Cuerpo Blindado del ejército de EE UU al servicio del gobierno de Gil-Robles. Portugal y la mitad occidental de España se convirtieron en una suerte de protectorado de Estados Unidos para «frenar a la ponzoña soviética en la Europa liberada». A cambio, ambos países fueron regados con el maná del Plan Marshall (1947-1951).

Postal conmemorativa de Valenciagrado, 1951.

Los doce millones de habitantes de la República Democrática fueron tentados a desertar del «yugo soviético» con la campaña de propaganda «Aquí vivimos mejor, ¡cruza!». Muchos siguieron el consejo, especialmente en las zonas fronterizas de Cataluña y el País Vasco, pero otros muchos perecieron en el intento de atravesar el Muro de la Libertad, erigido por el Gobierno republicano-soviético y que cruzaba España en diagonal como una gigantesca cicatriz que «podía verse desde el espacio», exageraba el generalato anticomunista.

De cualquier forma, la lejanía del poder de Moscú y la natural tendencia del español a tomarse a pitorreo la autoridad instauró en la España bolchevique una versión bastante descafeinada del régimen comunista de Europa del Este, más parecida a la Yugoslavia de Tito que a la Bulgaria de Dimitrov. Por ejemplo, los campos de reeducación de Teruel soportaban temperaturas de -20º, mucho más benevolentes que las que tenían que sufrir los sospechosos de desafección del Sóviet en Siberia. El régimen divulgó la falaz idea «Teruel no existe» para acallar las habladurías sobre el Gulag maño.

Mas no todo eran sinsabores en la mitad bolchevique de España: Ibizhenko se convirtió en un balneario para el descanso de los veteranos rusos de Stalingrado mientras BeniGrado se pobló de gigantescos edificios de hormigón para solaz de los obreros y campesinos del Soviet mediterráneo. De la Estación Espacial de Minglanilla (QenK) partió la primera misión tripulada espacial de la historia.

En 1981, anticipándose una década al desplome de la Unión Soviética, los máximos mandatarios de la España dividida, Suárez y Manglano, acordaron celebrar un referéndum conjunto sobre la reunificación. El «sí» barrió en ambos lados del muro y, 45 años después, España volvía a ser «Una, grande y libre», el eslogan consensuado para presentarse como una nación moderna ante la comunidad internacional.

¡Síguenos en Facetrambotic y en Twitterbotic!

The Chinese volunteers who fought in the Spanish civil war - their amazing courage and obscure fates.

Illiterate farmers, manual labourers, civil servants – some 100 Chinese joined the International Brigades helping fight General Franco’s fascists 80 years ago. Despite being few in number, they left a lasting impression

BY GARY JONES

15 JUL 2016

Xie Weijin (third from right at the back) with fellow inmates at Gurs internment camp, in France, in 1939.

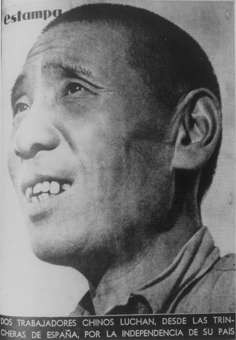

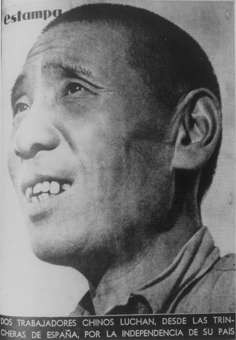

In the autumn of 1937, Zhang Ruishu was enjoying a rare break from his 14-hour days on the frontline. One of very few, if not the only, Chinese in Madrid, he hadn’t asked for time off – there was so much to do – but his commander had insisted he take a break. The Spanish capital was decorated with defiant if raggedy banners reading No pasarán (“They shall not pass”) and Madrid será la tumba del fascismo (“Madrid will be the tomb of fascism”). Zhang had seen many such signs before. At a newsstand, however, a large promotional poster for Spanish news magazine Estampa caught his eye.

Xie Weijin (left) and Zhang Ji (right) with a fellow Chinese in Spain, in 1938. Photo: courtesy of Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives

Xie Weijin (left) and Zhang Ji (right) with a fellow Chinese in Spain, in 1938. Photo: courtesy of Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives

The intriguing poster featured a man’s face in profile. It wasn’t a handsome face, but ruddy and weathered, with tightly cropped hair, hollow cheeks and a muddle of crooked teeth in a mouth set slightly agape – the face of a no-nonsense man who had known hardship. Suddenly, a crowd was gathering around Zhang; eyes were widening and fingers pointing. “That’s him!” they cried, lunging forward to shake the stranger’s hand.

The Chinese soldiers who fought in the American civil war

Almost 20 years to the day since he had first set foot on European soil, the humble 44-year-old from Shandong province, now a medic with Republican forces fighting fascism in the Spanish civil war, was being hailed as a hero in a country almost 10,000km from home.

Zhang Ruishu on the cover of Estampa magazine.

Zhang Ruishu on the cover of Estampa magazine.

Just over a year earlier, on July 17, 1936, at the same time as militaristic Japan was becoming increasingly assertive in China, a group of right-wing officers in the Spanish Army, led by General Francisco Franco, rose against the democratically elected Republican government. The move marked the beginning of a civil war that was to last for two years and eight months and provide a prelude to an even greater conflict in Europe.

While Franco’s Nationalists were openly assisted by the German and Italian forces of fascist dictators Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini, democratic nations including France and Britain operated an official policy of non-intervention, to the disgust of many of their own people, who saw the struggle as a fight against the evils of fascism and a prelude to even greater conflict in Europe.

Book review: Among the Headhunters - amazing true story of wartime grit in Burma

In response to their governments’ indifference, tens of thousands of workers, trade unionists and left-wing students mobilised and headed to Spain, to take up arms. The number of overseas combatants who fought in what came to be known as the International Brigades has been estimated at 40,000, with volunteers flooding in from 53 countries, including France (9,000 people), the United States (2,800), Britain (2,500), Poland (3,000) and even Germany (4,000) and Italy (3,000). They came from Costa Rica and Albania, from Greece, Cuba and Argentina, from Finland, Ireland, South Africa and Bulgaria.

And they came from China.

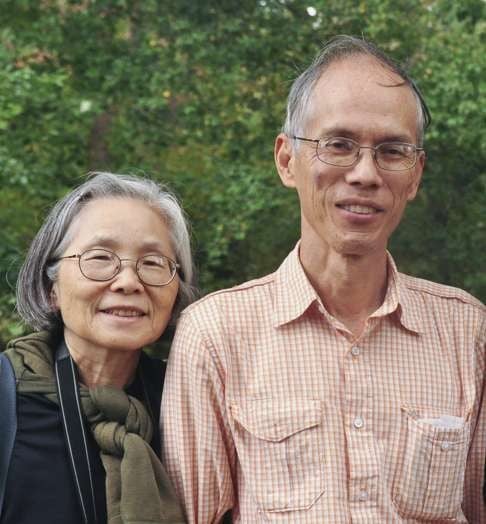

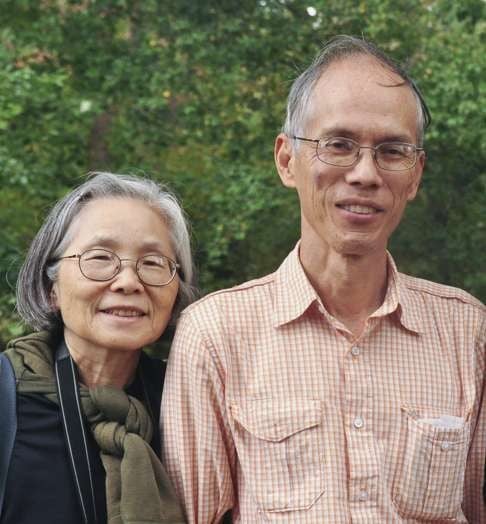

Hwei-Ru and Len Tsou.

Hwei-Ru and Len Tsou.

A multi-decade investigation by Len and Hwei-Ru Tsou, two American-Taiwanese research scientists (now retired and living in San Jose, California), has shown that more than 100 Chinese fought shoulder-to-shoulder with the Republicans. Some of their stories are detailed in the couple’s book, The Call of Spain: The Chinese Volunteers in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), which was first published in traditional Chinese in Taiwan in 2001 (and extended in 2015), and in Spanish and simplified Chinese in 2013, with new material to be added as it comes to light.

The Tsous’ call to arms was a documentary film made in the US.

Xie Weijin in Spain, as a soldier in the Spanish civil war.

Xie Weijin in Spain, as a soldier in the Spanish civil war.

“I think it would have been around 1986 when we saw The Good Fight,” says Len Tsou, pointing out that the documentary focused on the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, a battalion of American fighters that had travelled to Spain. “We were really surprised that so many volunteers from everywhere in the world had joined up. Our interest in the International Brigades started then, and we learned as much as we could.”

That year was the 50th anniversary of the war’s commencement, and Abraham Lincoln Brigade veterans published a brochure to mark the occasion. It contained a complete roster of the volunteers.

“Len and I looked through and there were three Chinese-looking names in there,” says Hwei-Ru Tsou. “We were so shocked. The Chinese at that time were fighting for their own survival – trying to push away the Japanese aggression.”

In love and war: a Hong Kong honeymoon for Ernest Hemingway and Martha Gellhorn

A seed had been sown, and the couple dug deeper. With many war veterans growing old, the researchers had to move fast, travelling many times to Spain, China, France, the Netherlands, Bulgaria, Germany and other countries to interview ex-soldiers, former volunteers, relatives and friends, and sifting through reams of official documents.

Bi Daowen (fourth from right) as a guest in Yanan of Mao Zedong (far right), in the 1940s.

Bi Daowen (fourth from right) as a guest in Yanan of Mao Zedong (far right), in the 1940s.

They discovered that the Chinese had come from all backgrounds, some from civil-servant families, others had been the lowliest of manual labourers and illiterate farmers. As their numbers had been relatively small, there had been no official Chinese brigade in Spain, and they fought in battalions from other nations, usually chosen depending on their language skills.

While Franco’s Nationalists had might on their side, the Republicans were not completely alone: they received material aid and more than 2,000 combat troops from the Soviet Union.

Mao Zedong sent an open letter of support to the Republicans in May 1937.

A banner from Zhu De, Zhou Enlai and Peng Dehuai supporting the Chinese volunteers fighting in the Spanish civil war.

A banner from Zhu De, Zhou Enlai and Peng Dehuai supporting the Chinese volunteers fighting in the Spanish civil war.

“If not for the fact that we have the Japanese enemy in front of us,” Mao wrote, “we would surely go join your troops.”

What Mao perhaps did not know was that, by then, a number of Chinese were already there.

Zhang’s road to Europe began as early as 1917, when – at the height of the first world war – Britain and France recruited more than 100,000 Chinese to labour in factories whose regular workforces were now fighting at the front. Born into extreme poverty in 1893, Zhang – orphaned since a teenager, jobless, illiterate and desperate – signed up, boarding a ship packed with almost 2,000 other Chinese men bound for Marseilles.

After a gruelling 70 days at sea, Zhang was put to work in a French paper mill. In less than a year, however, Germany had surrendered, the war ended and the Chinese workers were surplus to French requirements. The majority were shipped home.

With no family and no prospects back in China, Zhang decided to stay and try his luck, taking on the unpleasant and dangerous jobs (disinterring corpses and detonating unexploded gas bombs, for instance) that the French avoided.

Also hailing from Shandong, stout and plucky Liu Jingtian was born in 1890. After a stint in the Chinese army he too journeyed to France in 1917, remained when the war ended and, in 1924, he and Zhang (increasingly an autodidact now teaching himself French) secured steady employment at the Renault car-manufacturing plant in the western Paris suburb of Boulogne-Billancourt. Like many industrial workers at the time, they joined the French Communist Party and, when the Spanish civil war broke out, they were called upon to down tools, cross the Pyrenees on foot and slug it out with fascism.

Also hailing from Shandong, stout and plucky Liu Jingtian was born in 1890. After a stint in the Chinese army he too journeyed to France in 1917, remained when the war ended and, in 1924, he and Zhang (increasingly an autodidact now teaching himself French) secured steady employment at the Renault car-manufacturing plant in the western Paris suburb of Boulogne-Billancourt. Like many industrial workers at the time, they joined the French Communist Party and, when the Spanish civil war broke out, they were called upon to down tools, cross the Pyrenees on foot and slug it out with fascism.

Zhang and Liu arrived in Spain in November 1936, and though they asked to become International Brigade machine-gunners, their ages (both were in their 40s) saw them assigned to medical teams as stretcher-bearers, frequently charged with rescuing wounded soldiers while under fire. As described in Estampa, Zhang was wounded in the chest, shoulders and hands while discharging his duties. A dramatic, heat-of-battle photograph depicting Liu rescuing a wounded soldier was published in Spanish newspaper Frente Rojo, and he was lauded in print for his heroism.

“At the time, it was likely they would not get their [Renault] jobs back; they might not even be able to return to France,” says Hwei-Ru Tsou, “but they went anyway, because it was a very important fight. These two guys were not young, they were both single, and they said to themselves, ‘If the French workers are going, when they have families, they have children, then we are going, too.’ They were extraordinary, and so well loved by their comrades. They were so brave.”

A Republican fighter in Barcelona, in July 1936. Photo: AFP

A Republican fighter in Barcelona, in July 1936. Photo: AFP

Fighting with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, Zhang Ji from Minnesota and Chen Wenrao from New York were also originally from China. Chen, born in Guangdong province, was killed at the bloody Battle of Gandesa, in 1938, aged 25. Zhang, however, survived the war in Spain.

Coming from an educated family of relative privilege in Hunan province, Zhang Ji had left China for San Francisco in 1918, receiving a degree in mining engineering from the University of Minnesota in 1923. After the financial crash of 1929, he lost his job as an engineer and became radicalised, joining the Communist Party of the United States in 1935. In March 1937 – aged 37 – Zhang Ji boarded the SS Paris ocean liner in New York and headed for France, then crossed the Pyrenees into Spain. Tall, slim and ungainly, and not the physically strongest of volunteers, Zhang Ji was initially assigned as a truck driver, before taking desk duties.

Xie Weijin delivers a banner from strikers in Hong Kong to German Communist Party leader Ernst Thalmann in Berlin in 1927

Xie Weijin delivers a banner from strikers in Hong Kong to German Communist Party leader Ernst Thalmann in Berlin in 1927

Described in The Call of Spain as quiet and mysterious, Chinese-Indonesian doctor Bi Daowen (who also went by the Indonesian name Tio Oen Bik) of Java was 31 when he arrived in Spain, in September 1937, while one of the most fervently political of the Chinese was slight, bespectacled Xie Weijin, who was born in Sichuan province in 1899. Xie participated in the anti-imperialist May Fourth Movement in Shanghai in 1919 before heading for France.

In the 1920s, he joined the Communist Youth League in Europe and the Communist Party of China’s European Branch, and a photo taken at a meeting in Berlin in 1927 shows Xie handing over a banner reading “from the strike workers of Hong Kong and Kowloon” to the German communist leader Ernst Thälmann, who would be shot on Hitler’s orders in Buchenwald concentration camp in 1944.

Spanish Republicans armed against Nationalist rebels in the late 1930s. Photo: AFP

Spanish Republicans armed against Nationalist rebels in the late 1930s. Photo: AFP

A young Republican during the Spanish civil war. Photo: AFP

A young Republican during the Spanish civil war. Photo: AFP

Xie headed for Spain in April 1937. In a letter to the Communist Party of Spain, he wrote, “I came to Spain not for a short stay but to go to the battlefront. I will exert my utmost to fight as a soldier. I hope the committee will grant me this right and let me join the International Brigades just like many other foreign comrades.”

Xie was made a machine-gunner with the Austrian battalion but was removed from the frontline after being shot through his right leg, below the knee.

According to the Tsous’ research, Chen Agen was possibly the only Chinese volunteer who came to the war directly from China. Chen was, in fact, fleeing the authorities, having organised a trade union in Shanghai. While heading for Europe in 1937, a Vietnamese cook – rumoured to have been Ho Chi Minh – regaled Chen with tales of the anti-fascist derring-do in Spain, so he travelled there to fight, only to be captured and put to labour as a prisoner of war.

I felt that this great man had been forgotten, not only by his own people, Indonesian people, and his comrades, but also by the world

Hwei-Ru Tsou, author

With an arms embargo in place, according to the non-intervention policy of many countries, by 1938 the Republicans were in retreat, and in October the leadership ordered the withdrawal of the International Brigades in the hope of convincing the Nationalists’ foreign backers to withdraw their troops, but to no avail, and the war officially ended on April 1, 1939, with a Nationalist victory.

Photos: The Chinese Labour Corps in the first world war, July 25

The eventual fates of the International Brigade volunteers were as varied as their backgrounds.

Chen was not freed from jail until 1942, and his trail quickly went cold in Madrid. Zhang Ji fled Spain after the disbandment of the International Brigades and made it to Hong Kong, where in March 1939 his experiences of the Spanish civil war were published as “Spanish Vignettes” in the T’ien Hsia Monthly. Chang had written of his wish to join Mao’s Eighth Route Army when he got back to China, but it is unknown whether he succeeded – the Tsous have found no record of his whereabouts after Hong Kong.

Zhang Ruishi (second from left) and Liu Jingtian (second from right) with comrades from the 14th Brigade.

Zhang Ruishi (second from left) and Liu Jingtian (second from right) with comrades from the 14th Brigade.

Bi did make it to China and by 1940 he was in Yanan with Mao’s troops. Bi was one of the foreign volunteers who came to be revered as the “Spanish doctors”, supporting the Chinese war effort against Japan. The doctors had arrived in China from Poland, Germany, Canada, Britain, India and many other countries and had served on Spanish battlefields. Bi remained in Yanan until 1945 and the Japanese surrender, later working in the Soviet Union before returning to Indonesia, where he was ostracised for his revolutionary deeds and political beliefs. He was not heard from after 1966, one year after Suharto’s military coup, and Bi may have been executed.

“When I heard, I cried,” says Hwei-Ru Tsou. “I felt that I’d come to know him. He was so close to me. Later we learned so much about his endeavours, not only in Spain but also in China. I felt that this great man had been forgotten, not only by his own people, Indonesian people, and his comrades, but also by the world. He was a man who lived by his ideals, and that takes enormous courage. He was an unbelievable man.”

Republicans battle for the Alcazar in Toledo, Spain, in July 1936. Photo: AFP

Republicans battle for the Alcazar in Toledo, Spain, in July 1936. Photo: AFP

In early 1939, Xie was one of hundreds of thousands of Republican refugees who fled to France, where he was confined in the notorious Gurs internment camp for eight months before returning to China via Singapore, Hong Kong and Vietnam. Xie fought with the Red Army against the Japanese, eventually working as an engineer with the Chinese air force in the 1950s and early 60s. In 1965, however, Xie was purged from the Communist Party and labelled a revisionist due to his involvement with foreigners in Europe. He died of cancer in 1978, never having been rehabilitated.

Liu arrived in Yanan at the end of 1939 and was admitted to the Communist Party in 1946. It is known that he worked on construction projects, including the yaodong cave dwellings for which Yanan is famous, but then his trail went cold.

Q&A: The fates of 200,000 Chinese workers in Russia during the first world war

And the Estampa poster boy?

According to the Tsous, when the international volunteers retreated in 1938, Zhang Ruishu returned to Paris and was promptly arrested by the French government. Eventually released with help of the French Communist Party, his former co-workers and trade unionists at Renault paid for his passage by ship to China in 1939. After 1949, he worked in various administrative positions for the Xinhua News Agency, retiring in 1958. Ten years later, lonely and forgotten, he fell at the gate of his house, and died that same year, at the age of 75.

According to the Tsous, when the international volunteers retreated in 1938, Zhang Ruishu returned to Paris and was promptly arrested by the French government. Eventually released with help of the French Communist Party, his former co-workers and trade unionists at Renault paid for his passage by ship to China in 1939. After 1949, he worked in various administrative positions for the Xinhua News Agency, retiring in 1958. Ten years later, lonely and forgotten, he fell at the gate of his house, and died that same year, at the age of 75.

For Hwei-Ru Tsou, the experiences of the Chinese volunteers, who fought – and in some cases died – for their internationalist beliefs on the other side of the planet from their homeland, are not just mere history, but shining examples in a world regularly buffeted by political storms and growing intolerance.

“Their stories – in the current times – are so important,” She says. “The situation back then, with Hitler and Mussolini rising up in Europe, the economic and political situation at that time – that could return, and we see signs of that in some places in the world.

“These stories can serve to keep us alert.”

Xie Weijin (left) and Zhang Ji (right) with a fellow Chinese in Spain, in 1938. Photo: courtesy of Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives

Xie Weijin (left) and Zhang Ji (right) with a fellow Chinese in Spain, in 1938. Photo: courtesy of Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives Zhang Ruishu on the cover of Estampa magazine.

Zhang Ruishu on the cover of Estampa magazine. Hwei-Ru and Len Tsou.

Hwei-Ru and Len Tsou. Xie Weijin in Spain, as a soldier in the Spanish civil war.

Xie Weijin in Spain, as a soldier in the Spanish civil war. Bi Daowen (fourth from right) as a guest in Yanan of Mao Zedong (far right), in the 1940s.

Bi Daowen (fourth from right) as a guest in Yanan of Mao Zedong (far right), in the 1940s. A banner from Zhu De, Zhou Enlai and Peng Dehuai supporting the Chinese volunteers fighting in the Spanish civil war.

A banner from Zhu De, Zhou Enlai and Peng Dehuai supporting the Chinese volunteers fighting in the Spanish civil war. Also hailing from Shandong, stout and plucky Liu Jingtian was born in 1890. After a stint in the Chinese army he too journeyed to France in 1917, remained when the war ended and, in 1924, he and Zhang (increasingly an autodidact now teaching himself French) secured steady employment at the Renault car-manufacturing plant in the western Paris suburb of Boulogne-Billancourt. Like many industrial workers at the time, they joined the French Communist Party and, when the Spanish civil war broke out, they were called upon to down tools, cross the Pyrenees on foot and slug it out with fascism.

Also hailing from Shandong, stout and plucky Liu Jingtian was born in 1890. After a stint in the Chinese army he too journeyed to France in 1917, remained when the war ended and, in 1924, he and Zhang (increasingly an autodidact now teaching himself French) secured steady employment at the Renault car-manufacturing plant in the western Paris suburb of Boulogne-Billancourt. Like many industrial workers at the time, they joined the French Communist Party and, when the Spanish civil war broke out, they were called upon to down tools, cross the Pyrenees on foot and slug it out with fascism. A Republican fighter in Barcelona, in July 1936. Photo: AFP

A Republican fighter in Barcelona, in July 1936. Photo: AFP Xie Weijin delivers a banner from strikers in Hong Kong to German Communist Party leader Ernst Thalmann in Berlin in 1927

Xie Weijin delivers a banner from strikers in Hong Kong to German Communist Party leader Ernst Thalmann in Berlin in 1927 Spanish Republicans armed against Nationalist rebels in the late 1930s. Photo: AFP

Spanish Republicans armed against Nationalist rebels in the late 1930s. Photo: AFP A young Republican during the Spanish civil war. Photo: AFP

A young Republican during the Spanish civil war. Photo: AFP Zhang Ruishi (second from left) and Liu Jingtian (second from right) with comrades from the 14th Brigade.

Zhang Ruishi (second from left) and Liu Jingtian (second from right) with comrades from the 14th Brigade. Republicans battle for the Alcazar in Toledo, Spain, in July 1936. Photo: AFP

Republicans battle for the Alcazar in Toledo, Spain, in July 1936. Photo: AFP According to the Tsous, when the international volunteers retreated in 1938, Zhang Ruishu returned to Paris and was promptly arrested by the French government. Eventually released with help of the French Communist Party, his former co-workers and trade unionists at Renault paid for his passage by ship to China in 1939. After 1949, he worked in various administrative positions for the Xinhua News Agency, retiring in 1958. Ten years later, lonely and forgotten, he fell at the gate of his house, and died that same year, at the age of 75.

According to the Tsous, when the international volunteers retreated in 1938, Zhang Ruishu returned to Paris and was promptly arrested by the French government. Eventually released with help of the French Communist Party, his former co-workers and trade unionists at Renault paid for his passage by ship to China in 1939. After 1949, he worked in various administrative positions for the Xinhua News Agency, retiring in 1958. Ten years later, lonely and forgotten, he fell at the gate of his house, and died that same year, at the age of 75.